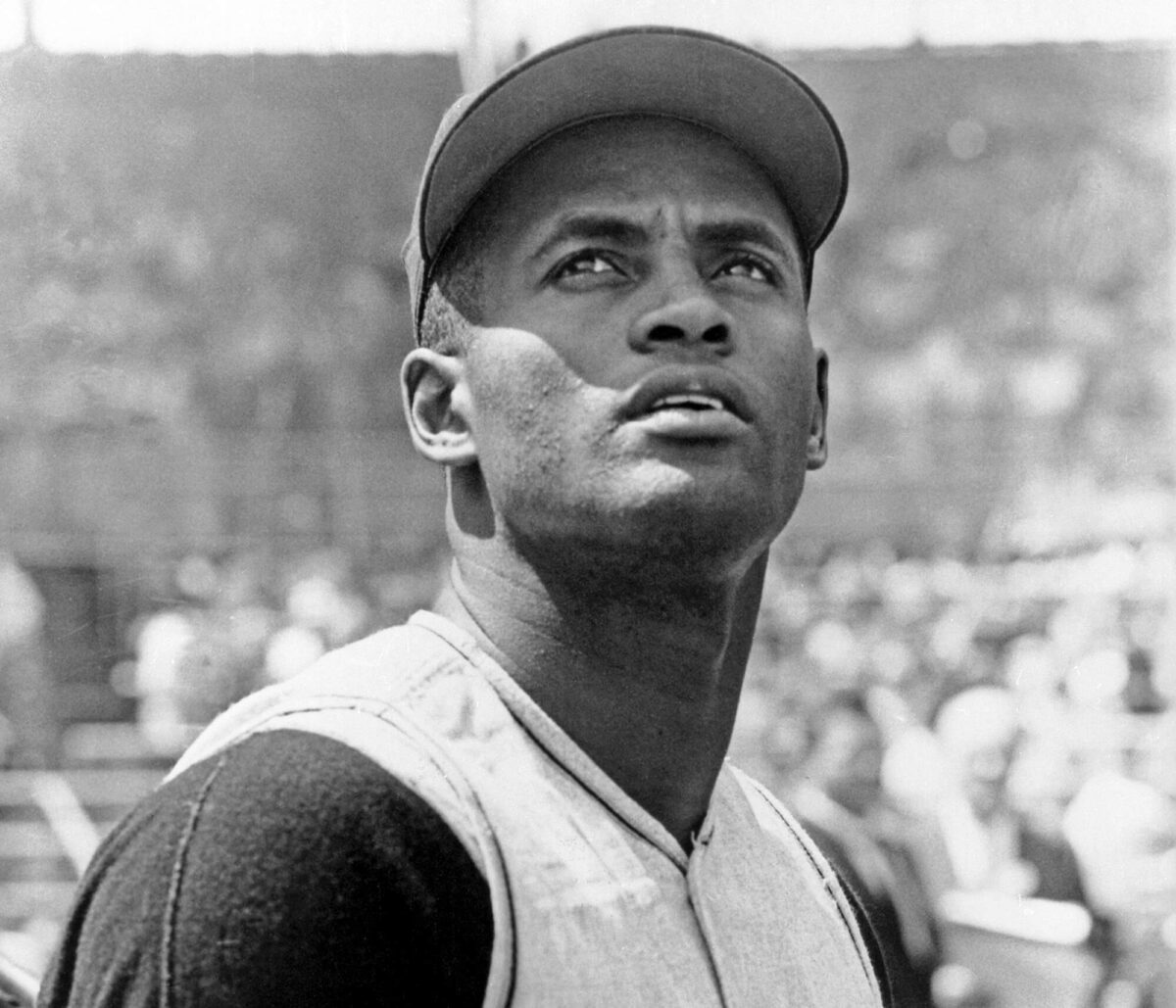

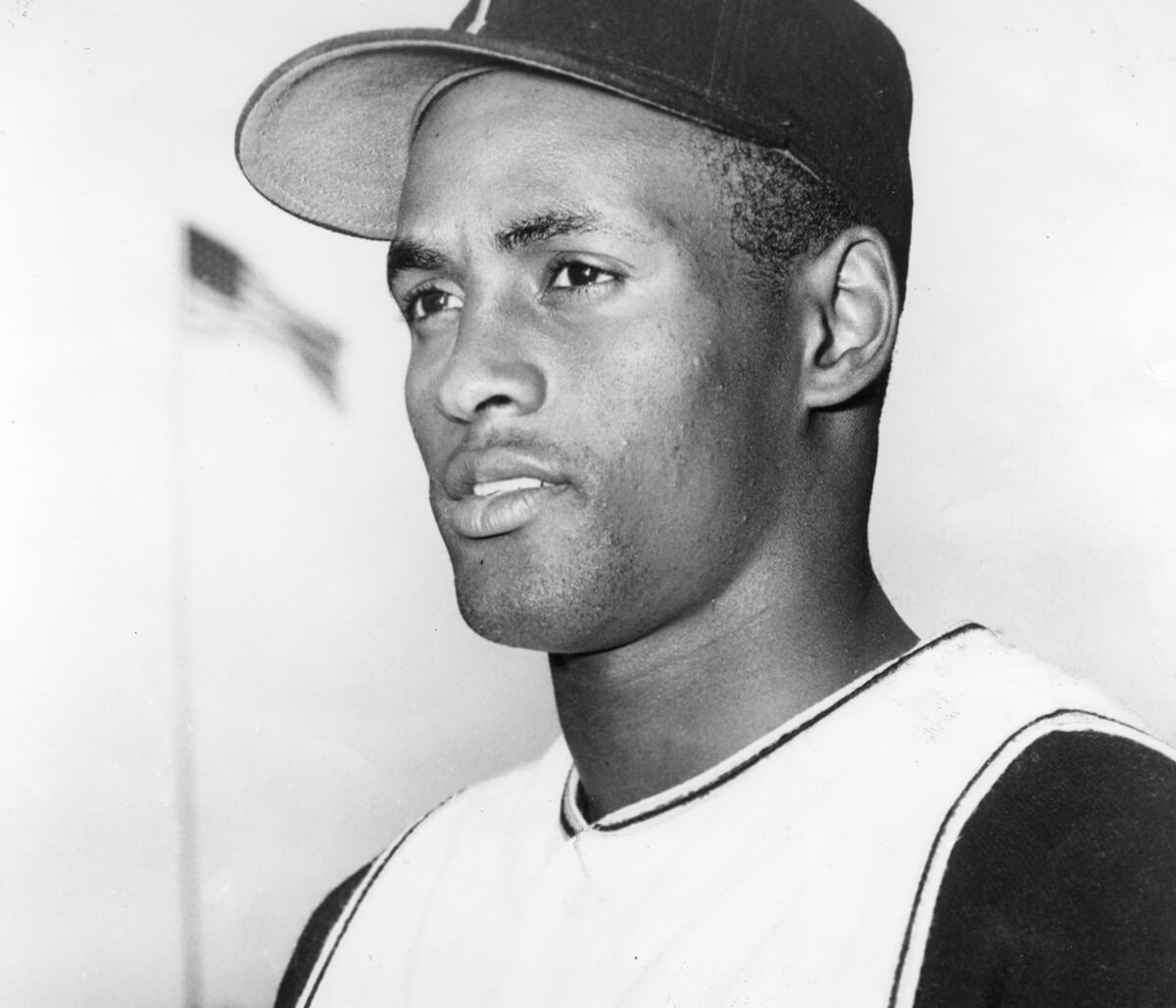

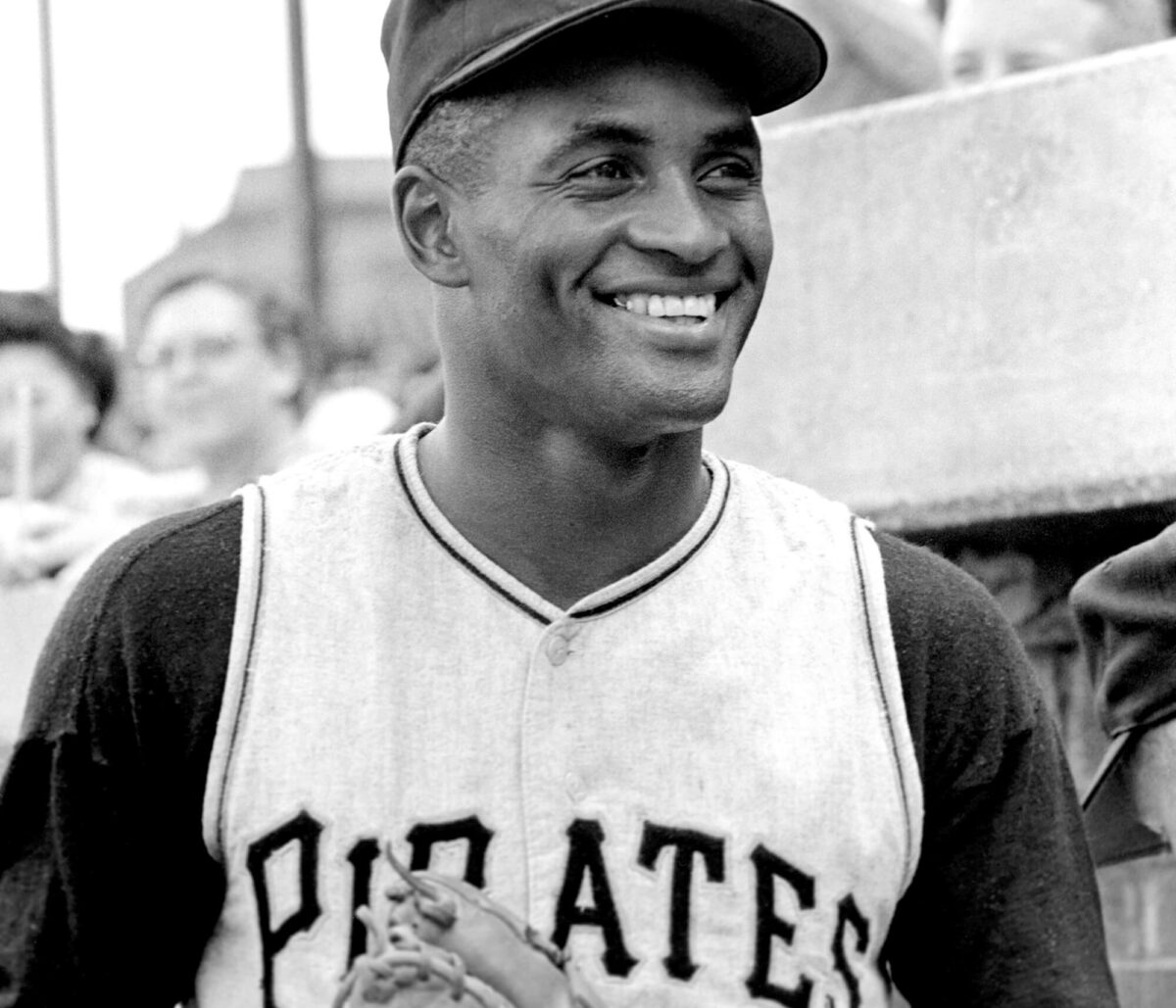

Roberto Enrique Clemente Walker is one of the greatest athletes and humanitarians of the 20th century.

For the people of Puerto Rico he is one of the ultimate symbols of national pride, not just for the records he set but for the lives he touched with his activism and with the simple power of watching someone from your community achieve excellence without compromising their character.

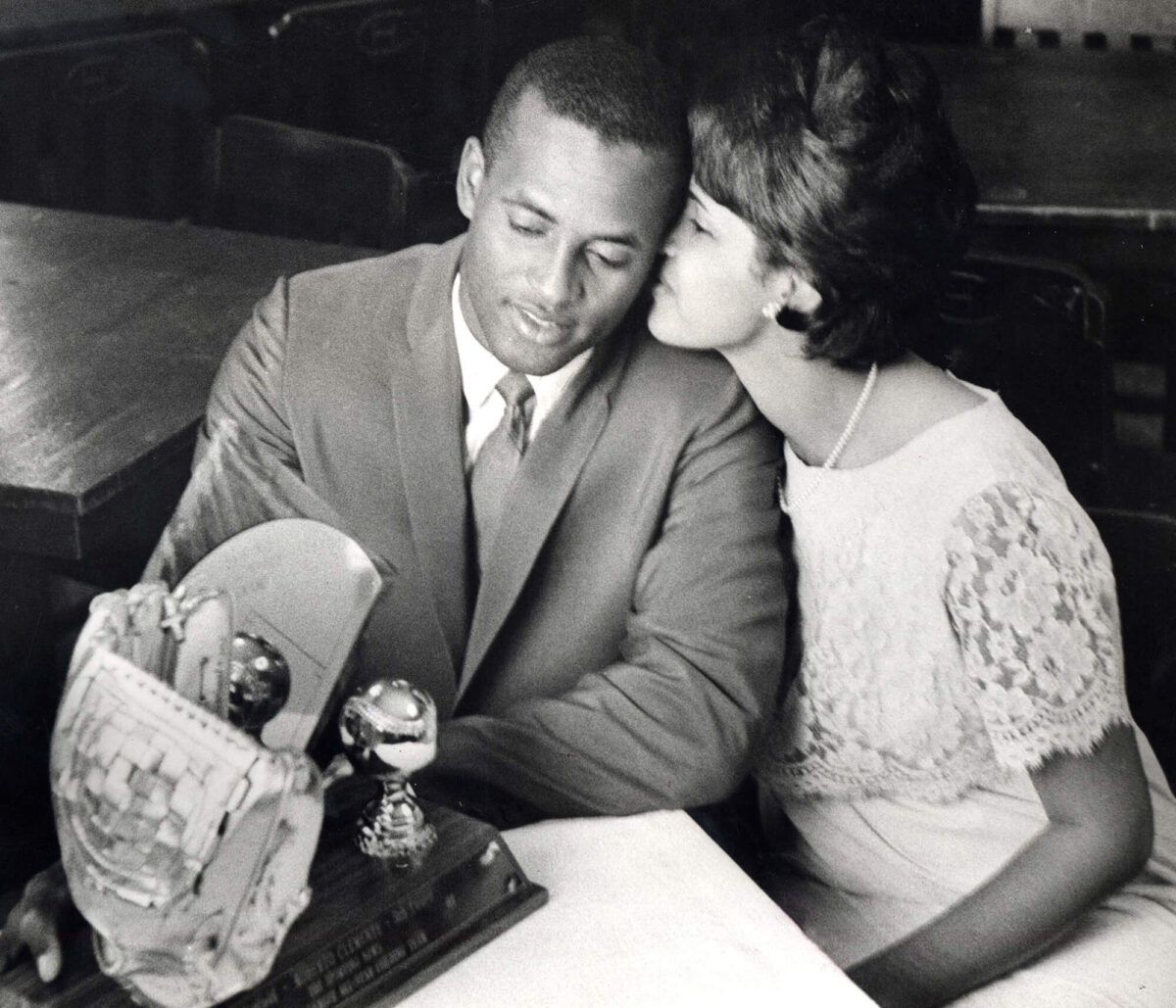

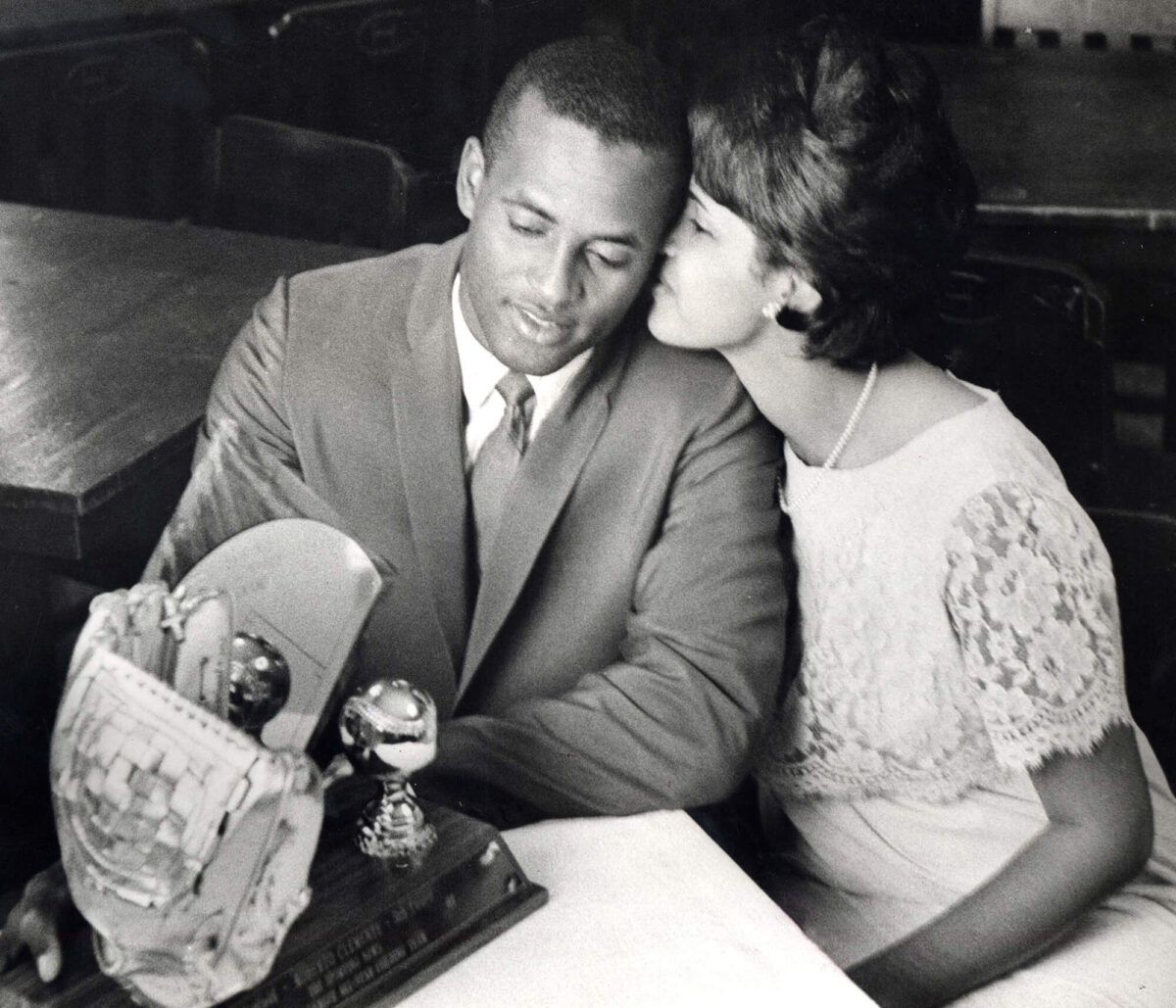

Four years after his first World Series win, Roberto Clemente married the love of his life, a humble bank secretary named Vera Cristina Zabala. She’s the strikingly beautiful woman seen at his side in hundreds of photos from that era, and she was his rock for the remainder of his career and life. Join us in celebrating this remarkable woman and learn about her vision for the Foundation.

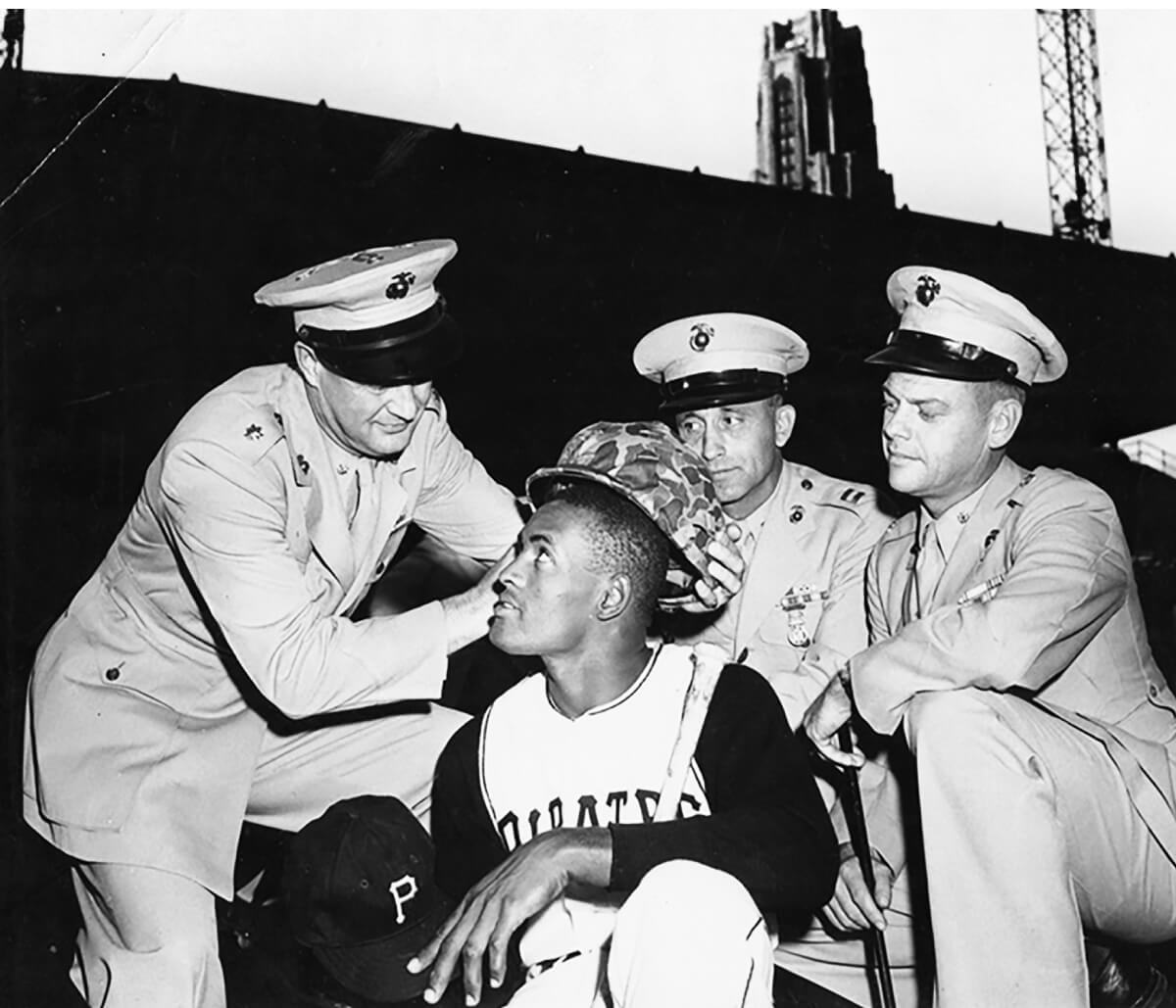

Roberto Clemente was a great ballplayer, humanitarian, husband, father, and son. What many don’t realize is that he was also a veteran of the United States Marine Corps.

Like all Puerto Ricans, Roberto was born an American citizen. After the 1958 baseball season, Roberto made the decision to enlist in the Marines, entering into a rich history of Puerto Rican military service.

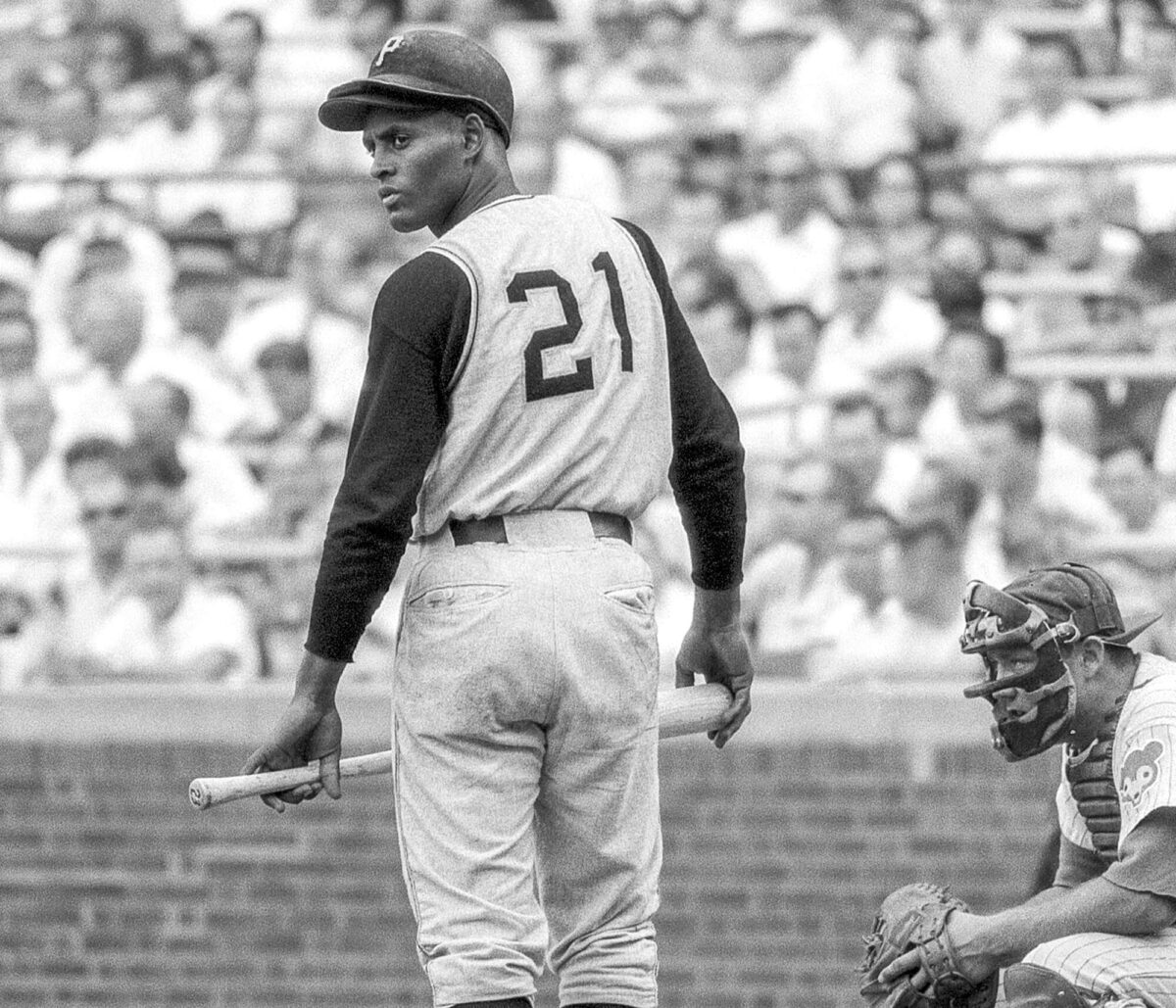

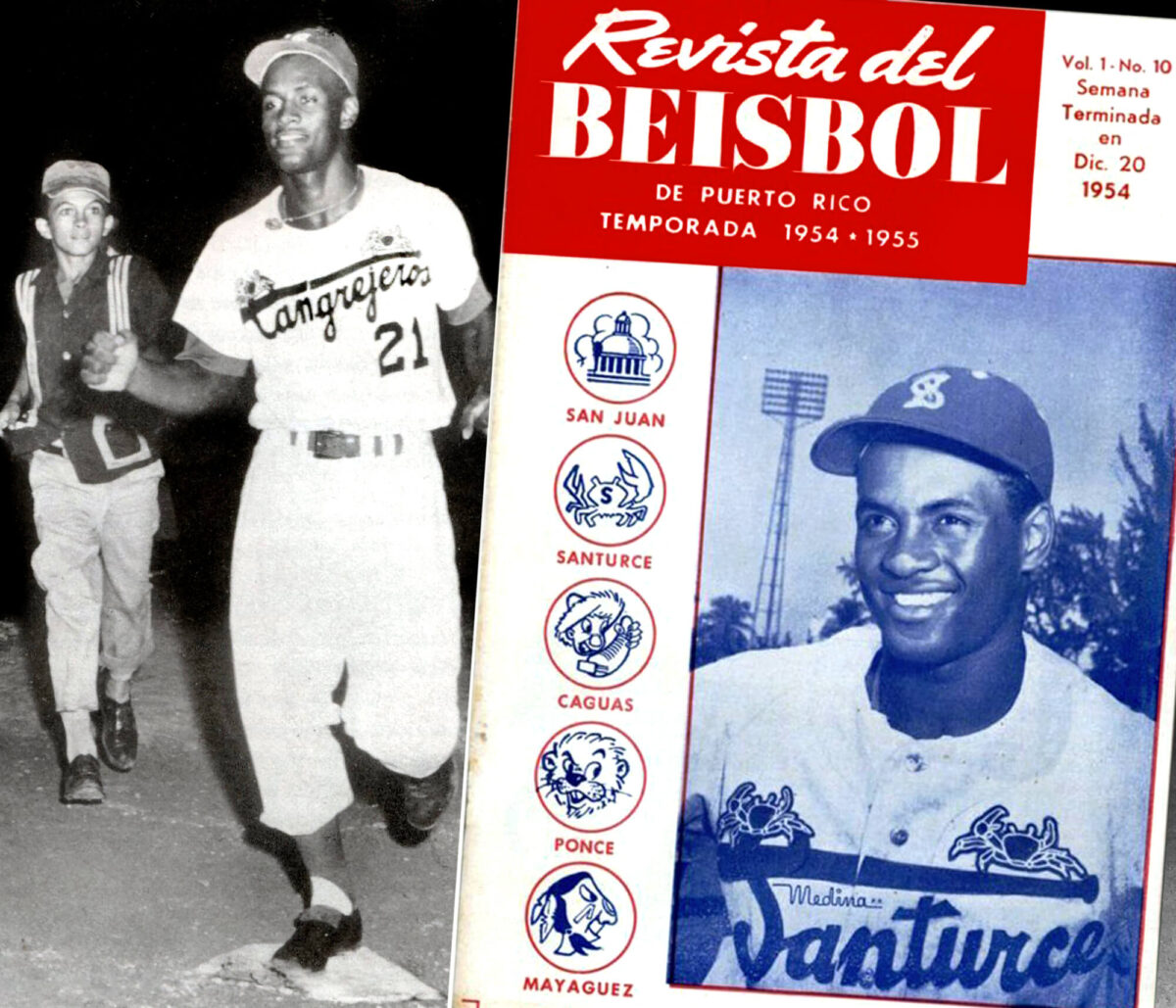

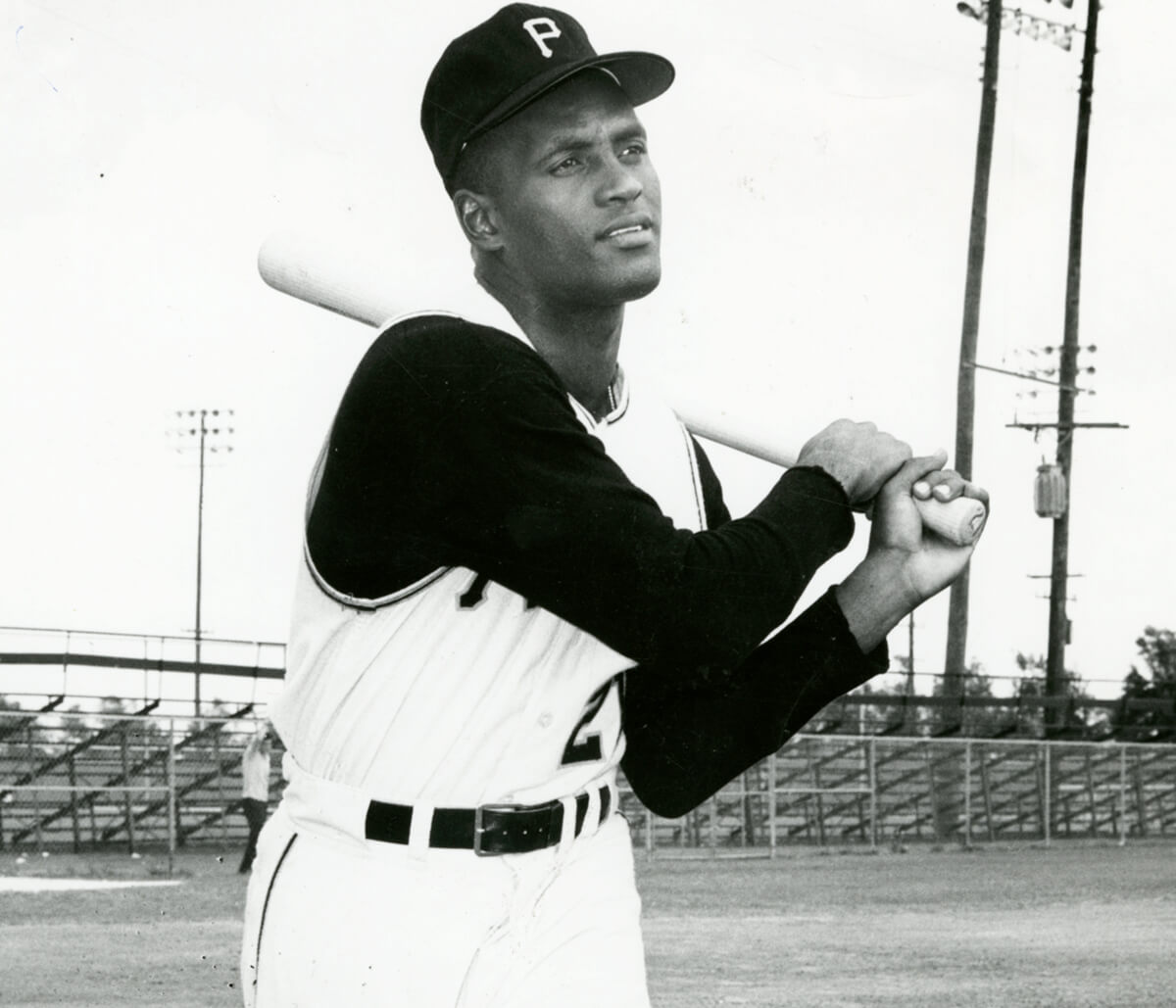

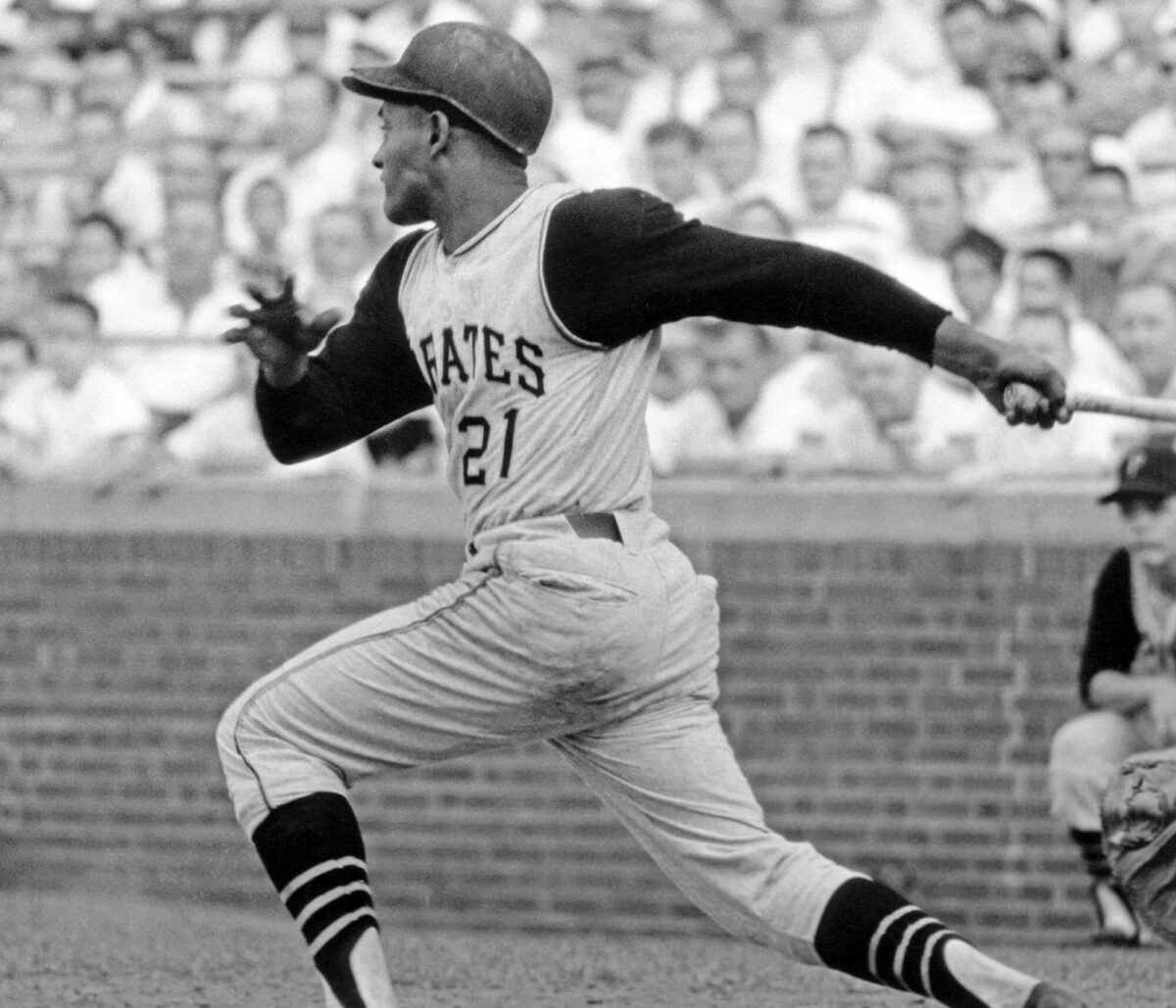

There are many iconic numbers in baseball, mostly the jersey numbers of famous players. Roberto Clemente will forever be associated with the number 21, Jackie Robinson with 42, Lou Gehrig with 4 (the first major league number to be retired), and so on.

When it comes to play statistics, there is a much higher number associated with a select few: 3,000.

21 holds a special significance in baseball, and particularly in Puerto Rican pop culture. But what makes it so special? From an arithmetic perspective, it’s made up of 3 sets of 7. Both of those numbers have a huge degree of significance in many religions, Christianity in particular.

It’s also half of 42, Jackie Robinson’s number. Maybe hearing and seeing the number, and internalizing its structure in association with Roberto (whose faith was strong), is part of the phenomenon. But it may be even simpler: people love Roberto Clemente, and 21 is an immediately recognizable shorthand to express that admiration.

Last September marked the 52nd anniversary of Roberto’s 3,000th hit. One of baseball’s most triumphant moments, the crown jewel of baseball’s most beloved player. But for Roberto it wasn’t all about the records broken and games won. It was about his service to humanity. He once said that he wanted

“to be remembered as a ballplayer who gave all he had to give.”

His statement wasn’t specific to baseball. Roberto considered himself, first and foremost, a servant to humanity.

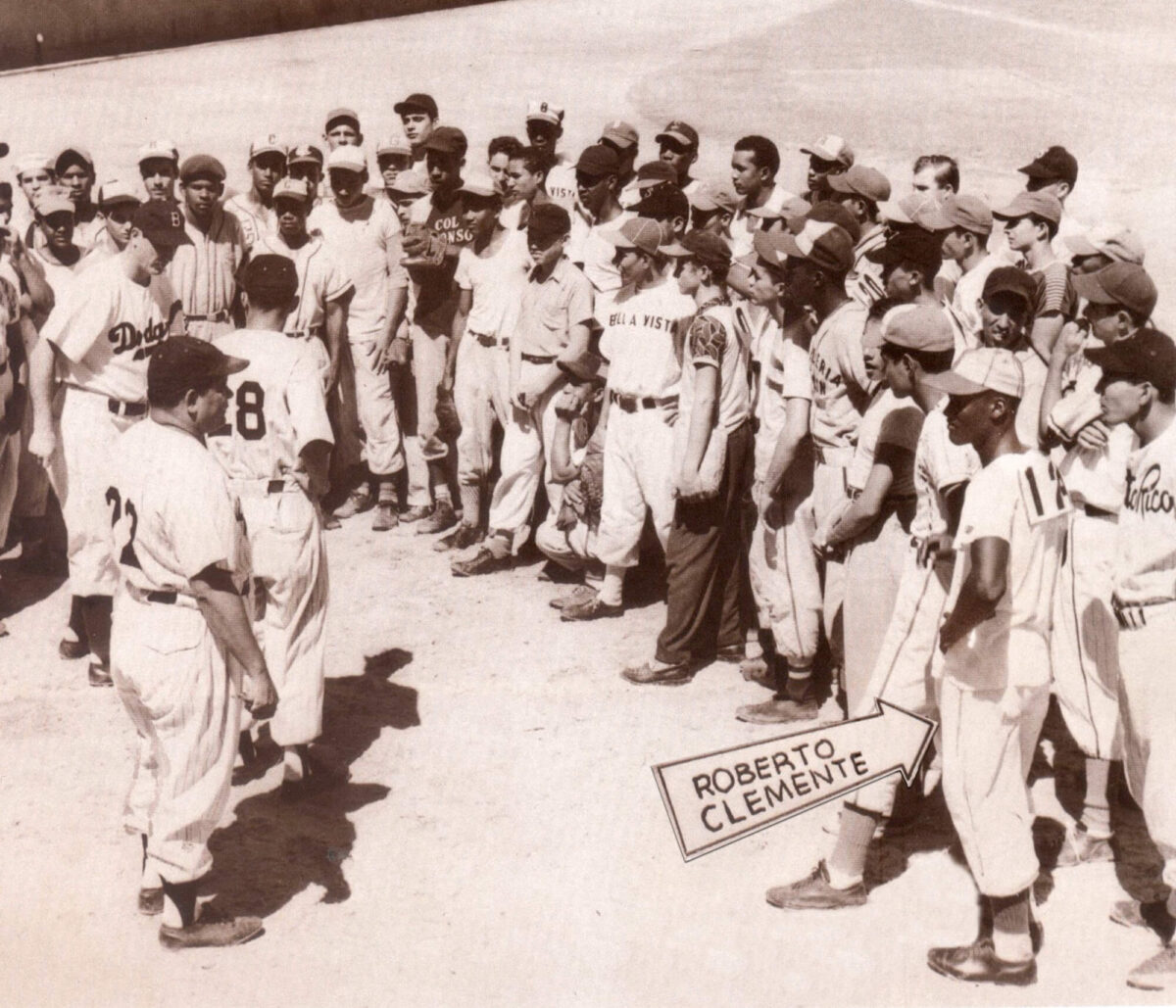

Born August 18, 1934 to a laundress named Luisa Walker in Barrio San Antón, Carolina, he went from loading trucks on a sugarcane plantation for his father, Melchor Clemente, to beginning his career with the Puerto Rican Professional Baseball League at just 17 years old.

Roberto’s all-around talent for sports was visible early on. He excelled in the high jump and javelin throw at Vizcarrondo High School, and there was talk that he might be good enough for the Olympics. But baseball was his true passion, and he could often be seen with a rubber ball in hand, flexing to improve his grip.

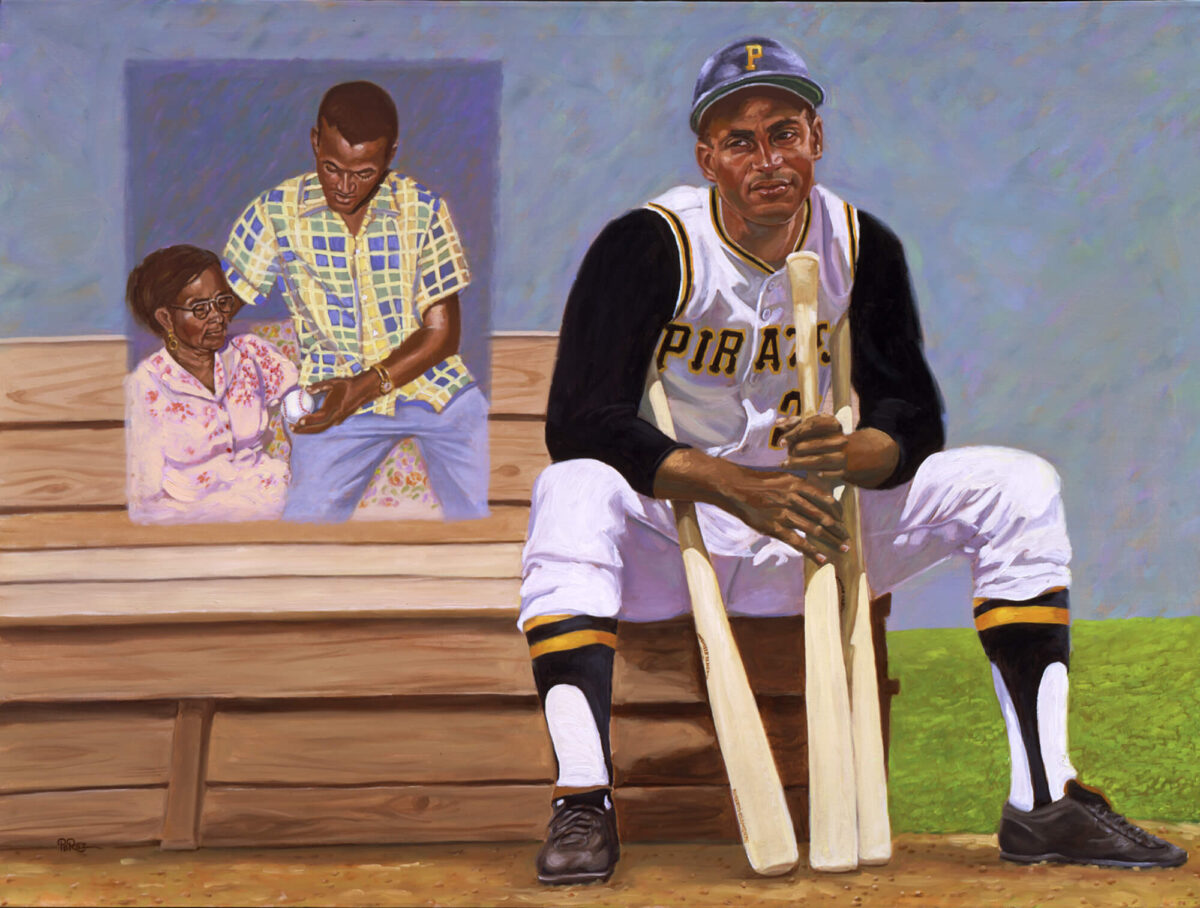

Sports commentators often invoked industrial imagery when describing Roberto’s arm; it was a “gun,” a “rifle,” a “weapon” renowned for its laser precision and raw power. He would often claim that his mother Luisa had just as powerful an arm as his, which is actually believable given her life of arduous manual labor. Despite having little time for herself, she gifted her son with a lifelong passion for baseball.

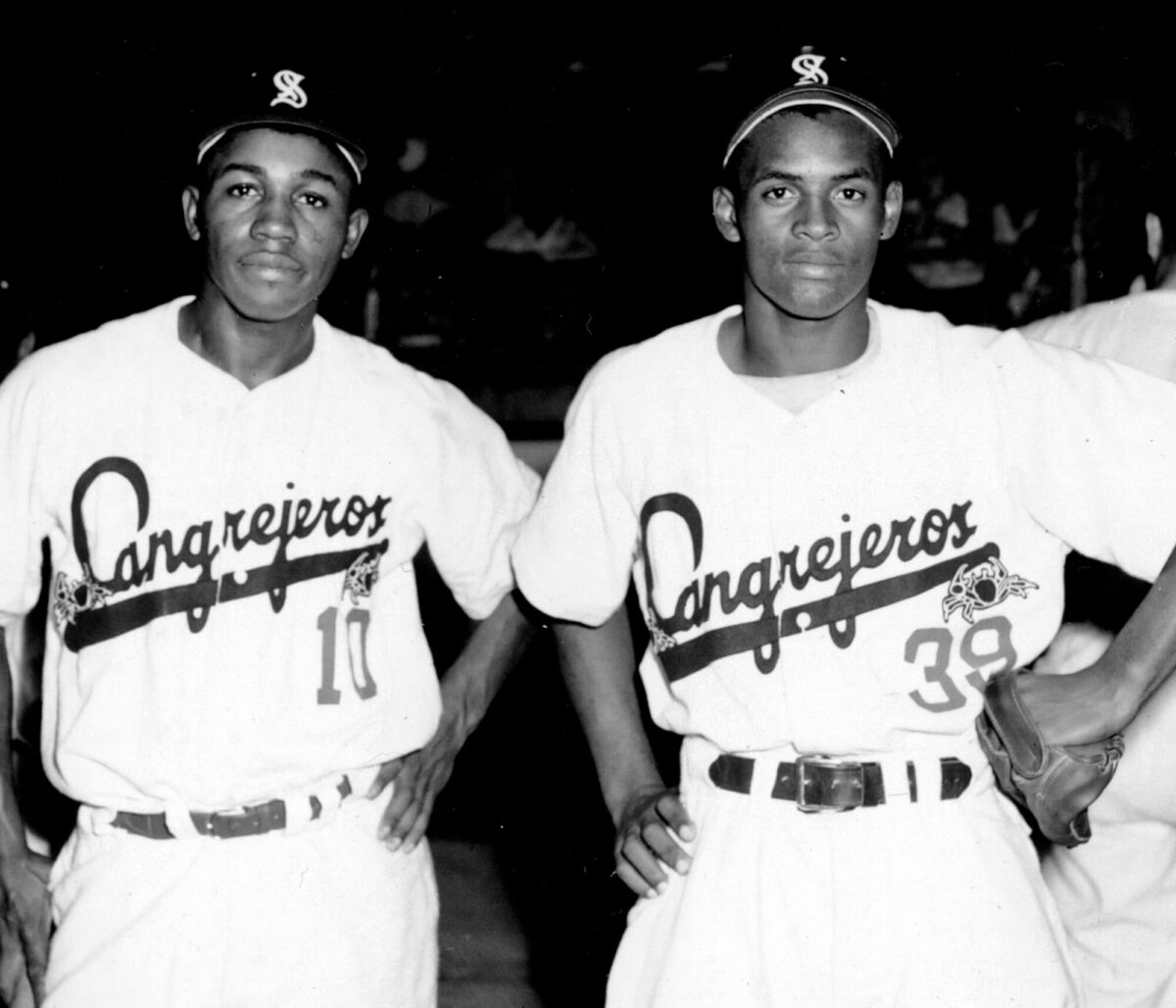

Roberto’s professional idol was Monte Irvin, a pioneering Black leftfielder and first baseman who wintered in Puerto Rico, playing for the Senadores de San Juan (San Juan Senators). Roberto and his friends would carry the Senators’ bags and get into the field for free. Monte remembered the youngster fondly and gave him a ball and glove as gifts, though he didn’t see him play until much later.

The combined influence of Monte and Luisa inspired Roberto to pursue his baseball dream, and his javelin experience was visible in how he understood the physics of the ball and his body. He certainly made an impression when the Dodgers sent Al Campanis to Puerto Rico to scout for talent.

At Campanis’s urging (he called Roberto the “best free-agent athlete I’ve ever seen”), the Dodgers offered Roberto a $5000 salary with $10000 bonus to sign with them in 1954. Melchor told a local newspaper that, if the Dodgers didn’t pay him sufficiently, Roberto would study engineering in Mayagüez instead.

Sensing an opportunity, Luis Olmo of the Braves approached Roberto with a $30000 offer. He went to his parents for advice, and Luisa recommended that he sign with whoever he gave his word to first. By staying true to his word and signing with the Dodgers, the 18-year-old Roberto built his professional career on an honorable foundation.

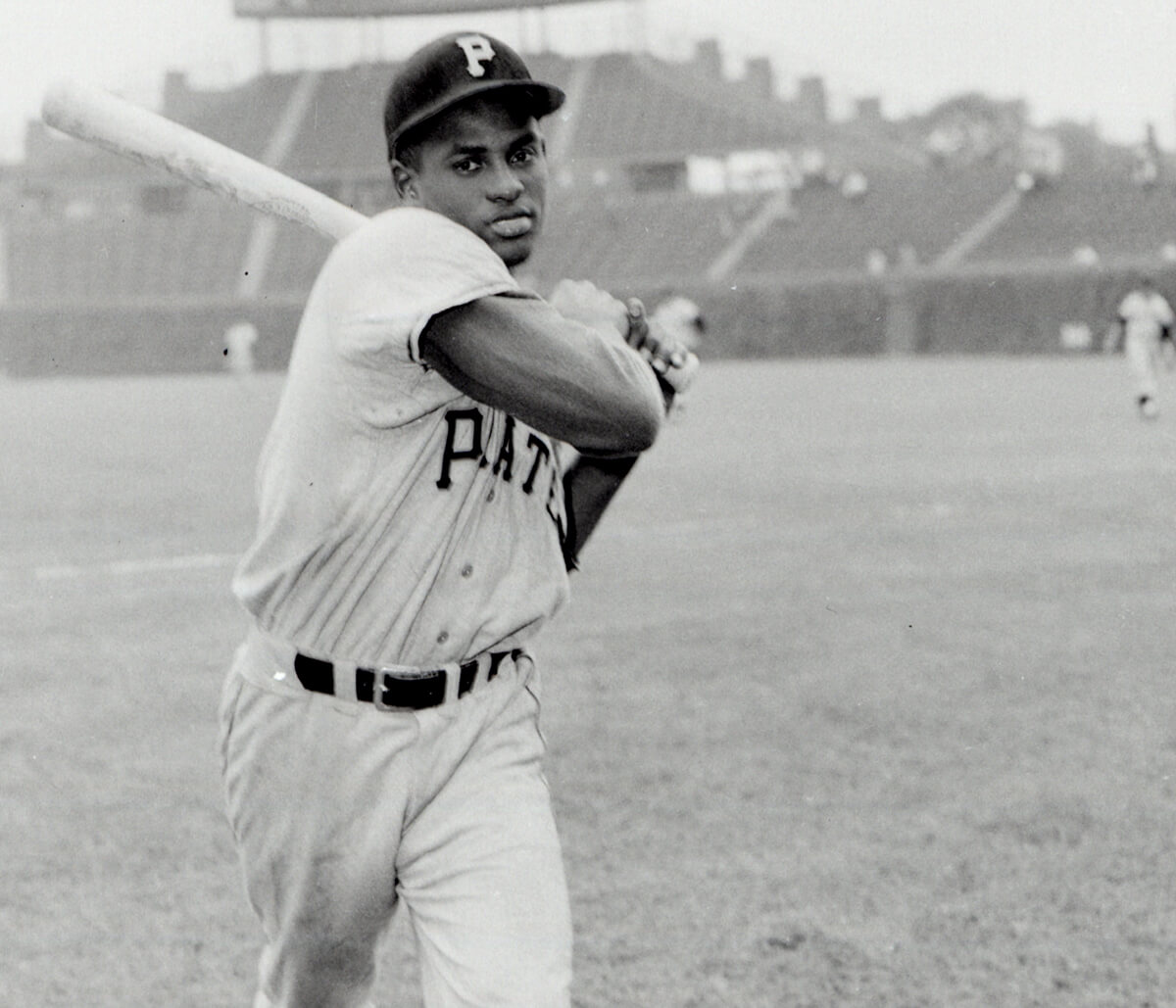

It was a rough and frustrating journey from the Dodgers to the Pirates, and to fame. An arcane rule was in effect at the time that basically stranded young signees on the bench for entire seasons. Even though they risked losing Roberto in the offseason draft, the Dodgers assigned him to the International League during the ’54 season, playing for the Montreal Royals.

Later, Roberto stated to the press that he believes the Dodgers “hid” him in Montreal, which has become the conventional understanding. But Roberto’s talent was already well-known to the baseball community, and the Dodgers had to outbid the Giants, Braves, Red Sox, and Cardinals to sign him in the first place.

In all probability, the deciding factors were experience and race. Roberto was very “green,” very new when he was signed, and the Dodgers’ pool of outfielders was crowded. He had bypassed normal Minor League tiers without having a chance to hone his skills.

There was also concern in the office that “too many minorities” on the field may upset white players and fans. The situation was such that, had Roberto stayed with the Dodgers, he could have been lost in the team’s dense pool of talent and we wouldn’t be talking about him today. In Montreal, Roberto had so few opportunities to play that he struggled to perform consistently, and press reports from the time rarely mention him.

When the team traveled to Richmond, Virginia for games, Roberto encountered Jim Crow laws for the first time when the black players had to stay at a separate hotel. There was no segregation in Canadian baseball, at least not officially, and he had grown up idolizing the Negro League players who would play on the island in winter.

In the Deep South, he quickly learned that these great players were being deliberately ignored by many Americans, 8 years after Jackie Robinson broke the color line. It was an awakening he would never forget.

Though the Dodgers wanted to keep him, it was the Pittsburgh Pirates who had first pick in the 1954 offseason draft due to their low performance that year. Clyde Sukeforth was in Montreal on behalf of Branch Rickey, the man who signed Jackie to the Dodgers and had become the Pirates’ new general manager.

Sukeforth was blown away by what little of Roberto he got to see, and made sure he was at the top of their priority list. Branch Rickey Jr. was sent to the drafting meeting, where he crushed the dreams of every suit in the room by selecting Clemente.

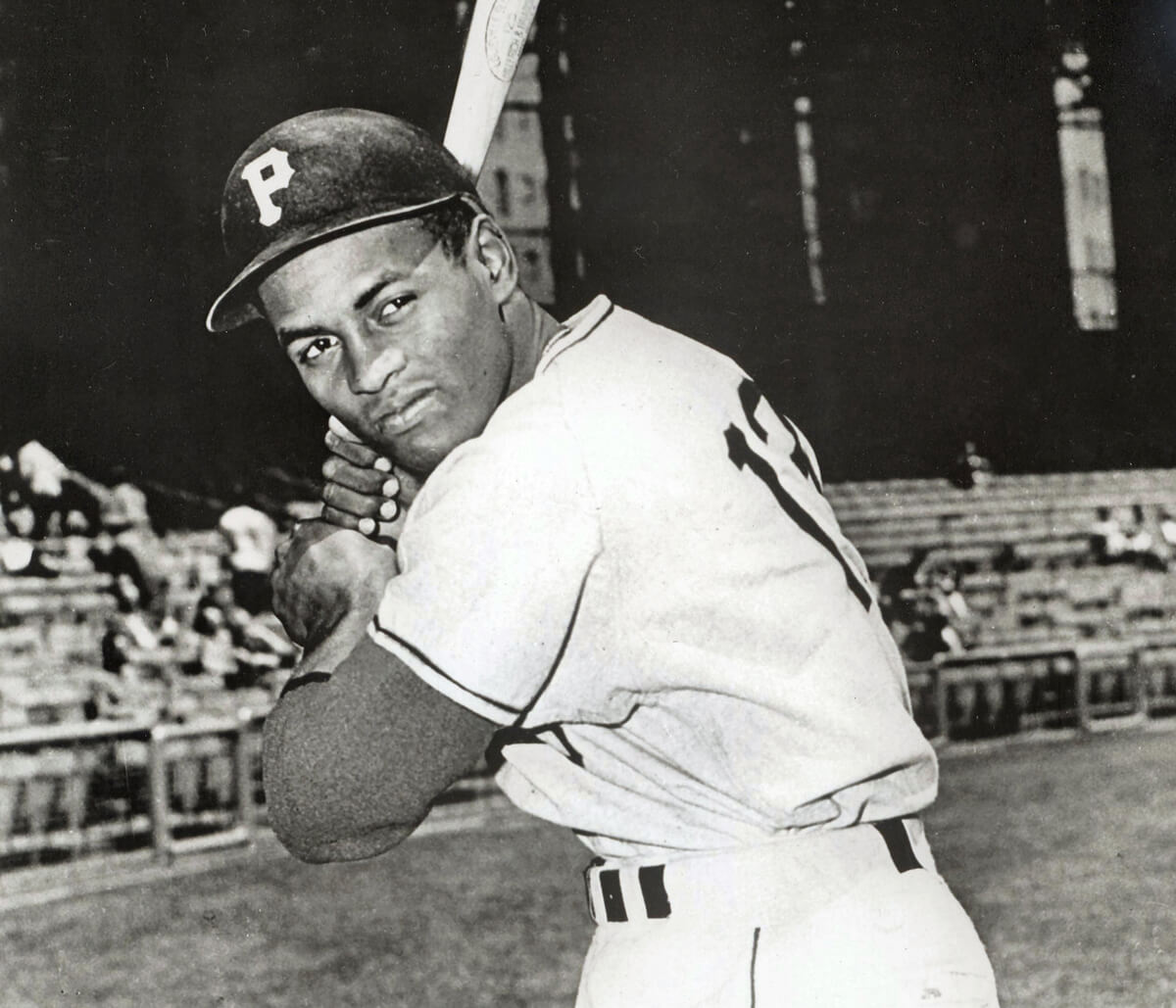

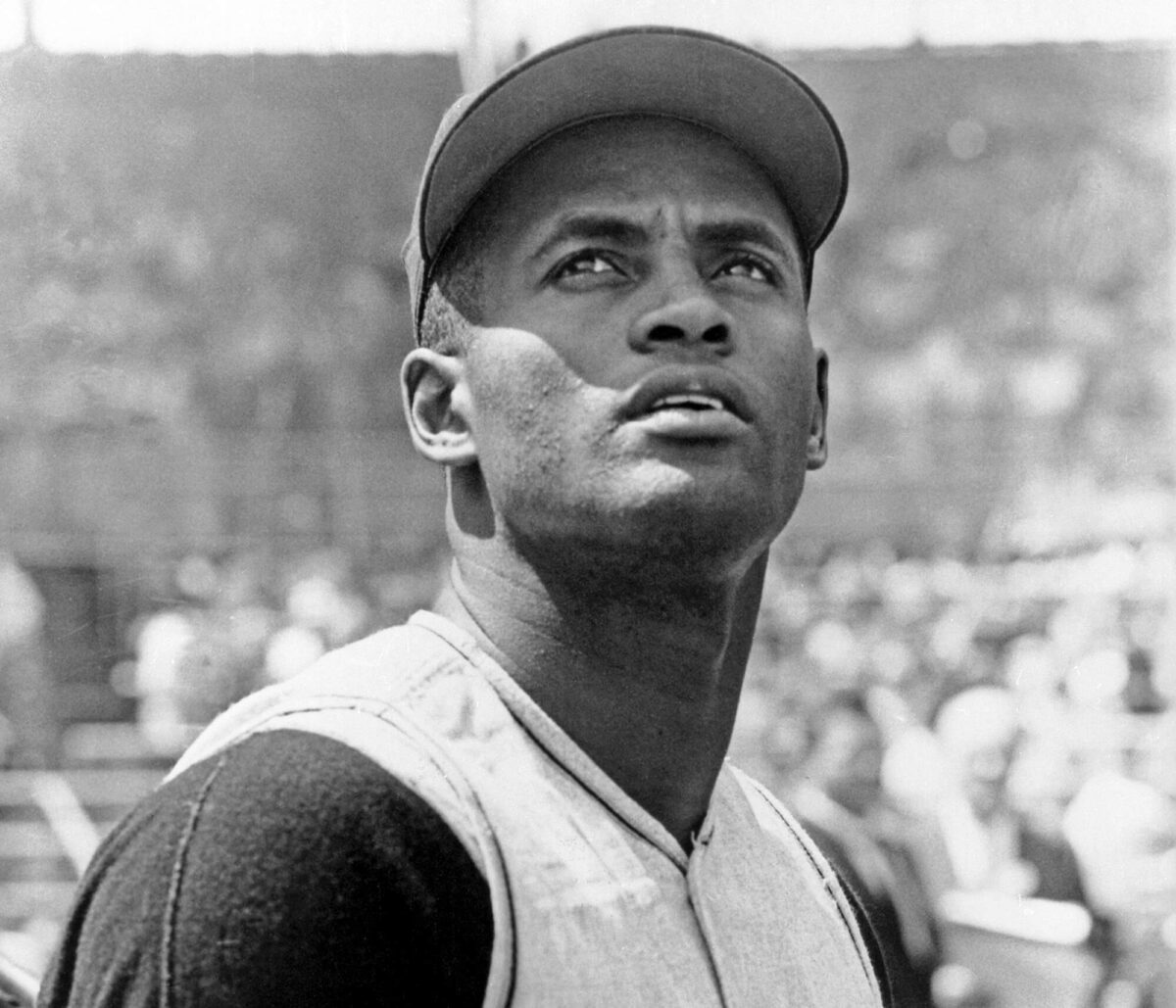

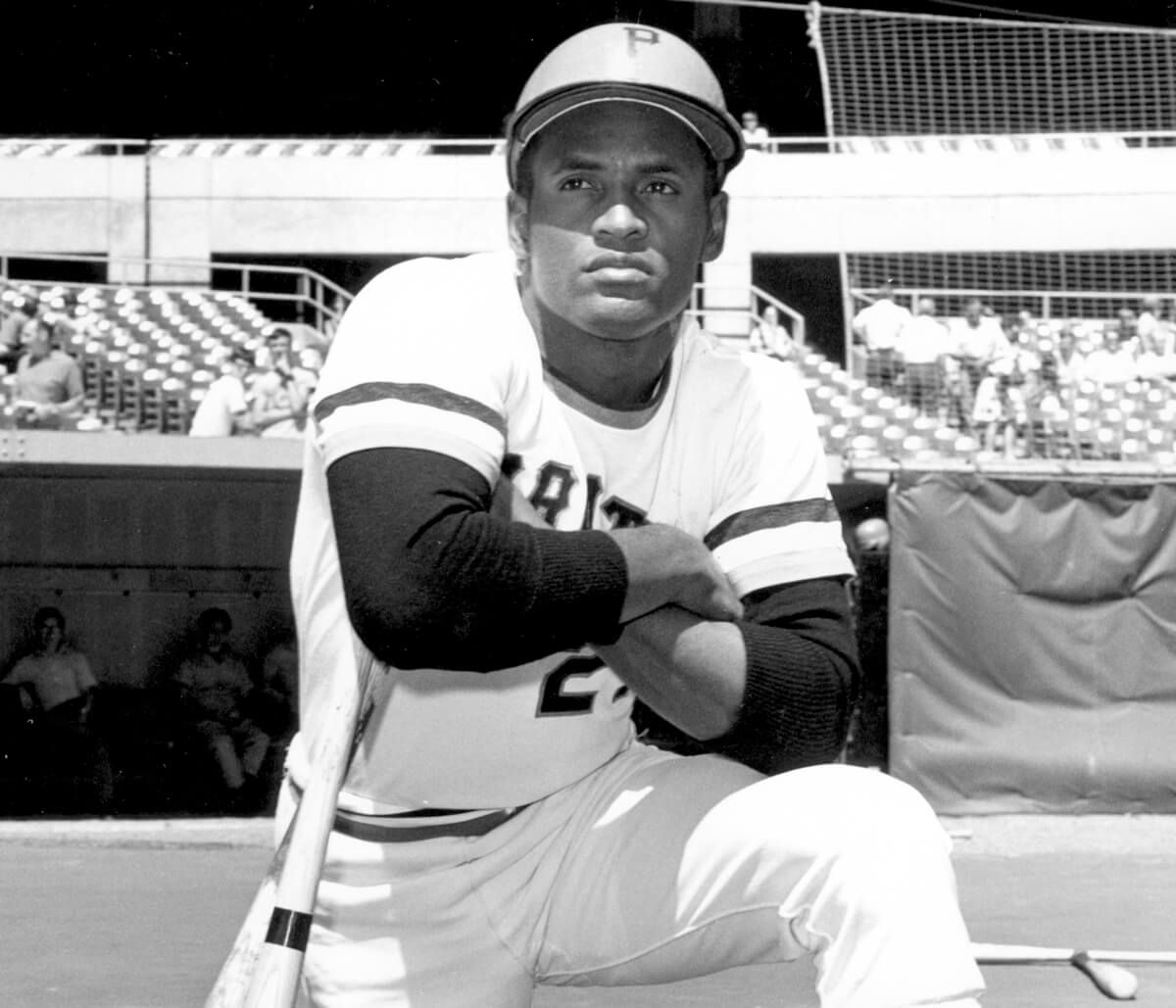

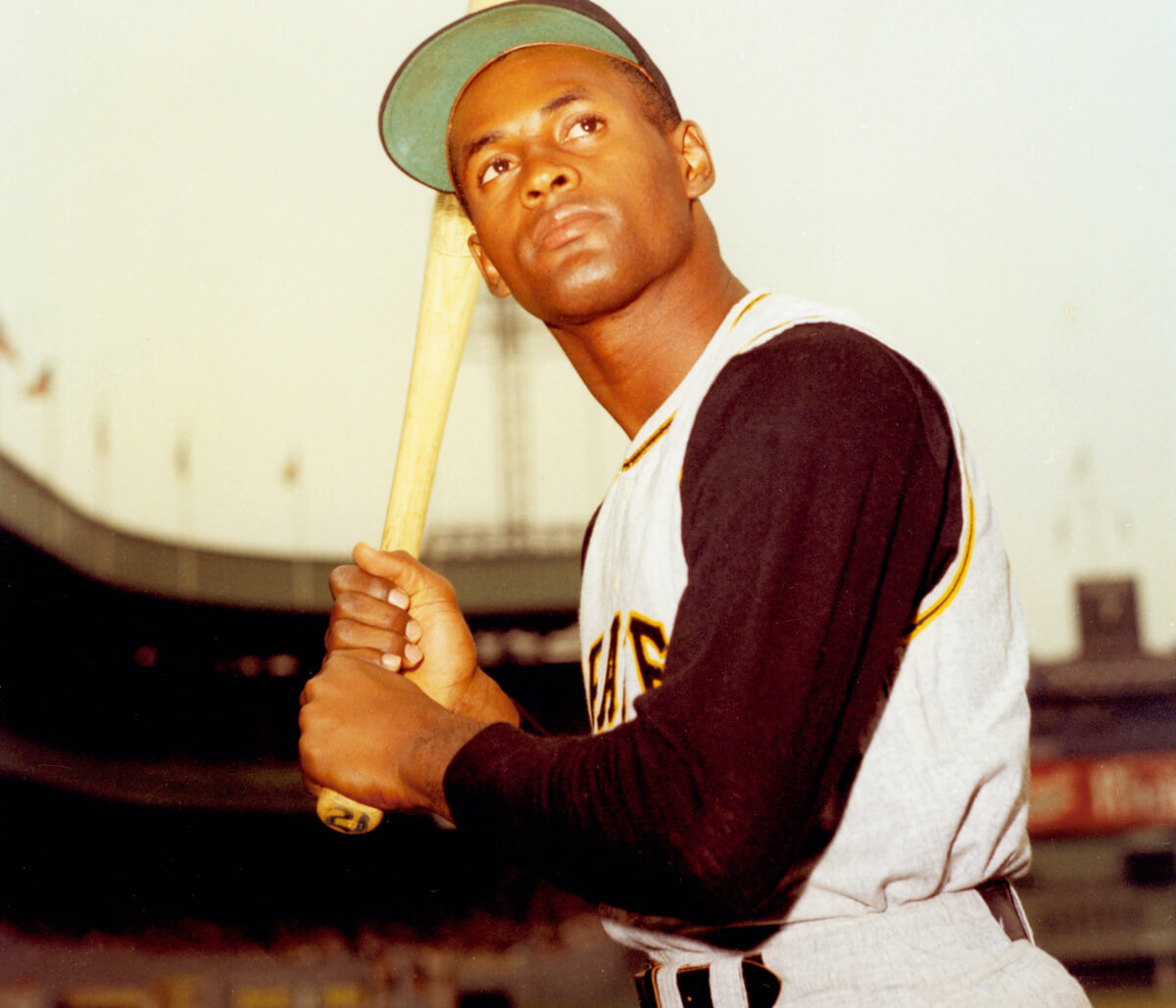

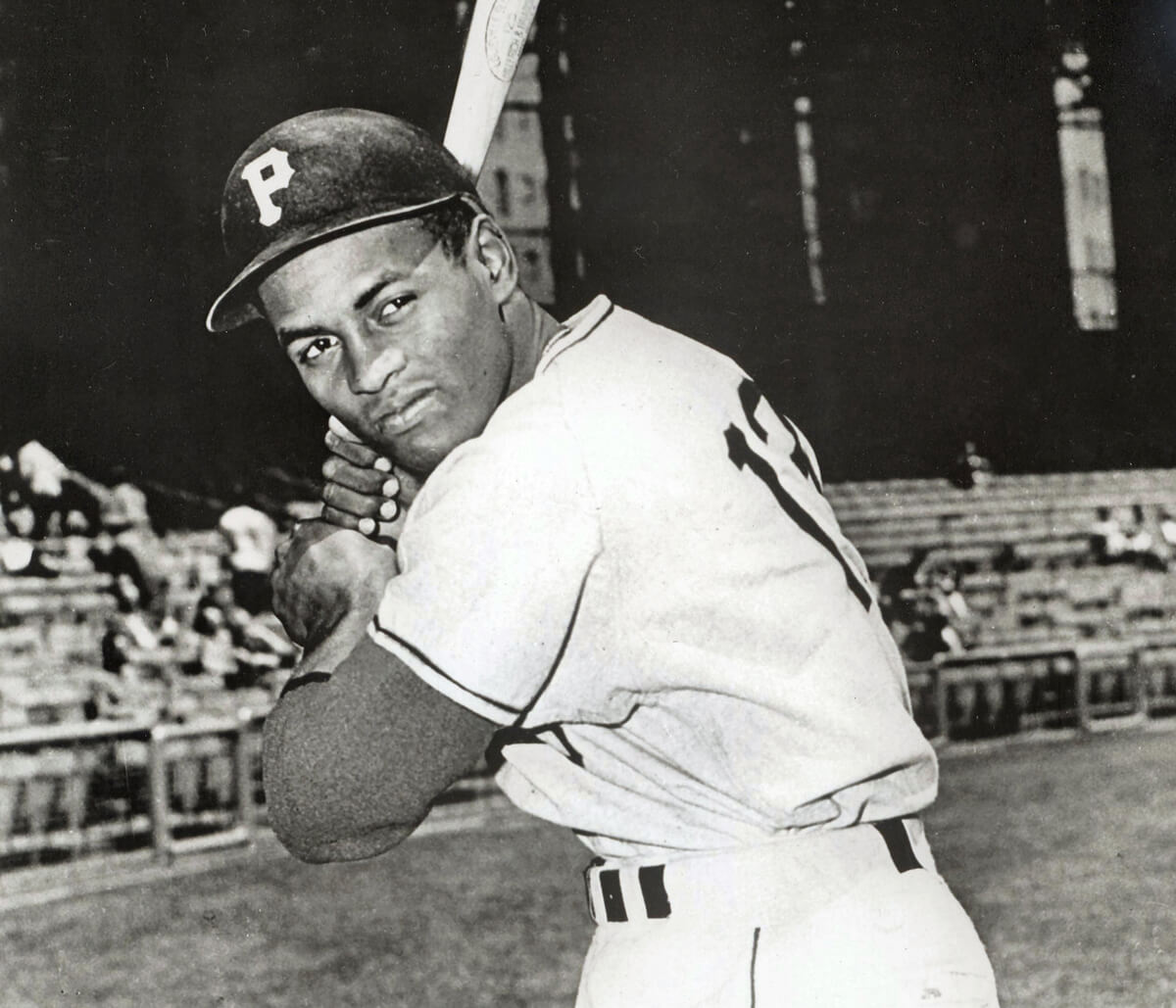

Later he received his iconic number 21, and he would dominate the game throughout the 60’s and inscribe the number into sporting legend forever. It was a mythic time, and the rhetoric used to describe him reflects that. One announcer remarked that “Clemente in the outfield was an epic poem,” putting him in a class with the ancient heroes of Homer and Virgil, while teammate Dick Groat observed that he “was built like a Greek god.”

The prologue of David Maraniss’s definitive biography is titled “Memory and Myth,” and books about Clemente are notoriously spotty in their balance of truth and fiction. In a period perceived as a second “dead-ball” era, it was easy to see top performers like Mays, Aaron, Mantle, and Clemente as titans.

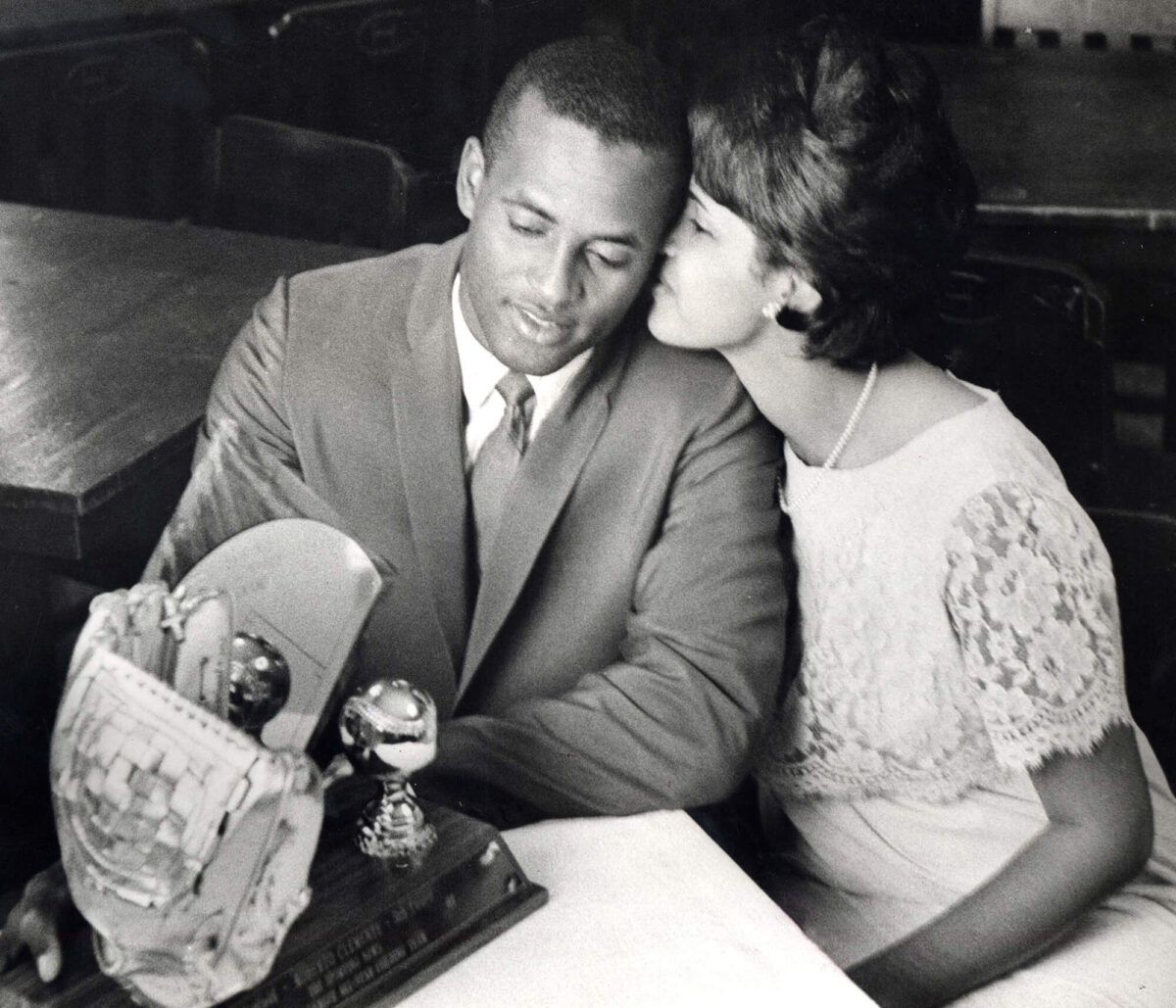

Unlike the heroes of antiquity, Roberto didn’t leave his family out of the quest. He and Vera Zabala grew up in the same area at the same time, but they didn’t meet until three years after his first World Series win. The first time their paths crossed, her brother was giving her a ride and they passed Roberto in his white Cadillac.

She recognized his face from the paper, while he didn’t notice her at all. Roberto was a well-established hometown hero, so in theory he could have swept her off her feet with his wealth and star status. He wasn’t that kind of man, and she wasn’t that kind of woman.

The second time, the tables were turned. Roberto saw Vera on the street, making a trip to the drugstore, and he asked the clerk who she was after she left. From there he courted her respectfully after seeking out her parents’ approval. The Zabalas were suspicious at first, but it became clear that Roberto was somehow uncorrupted by his celebrity.

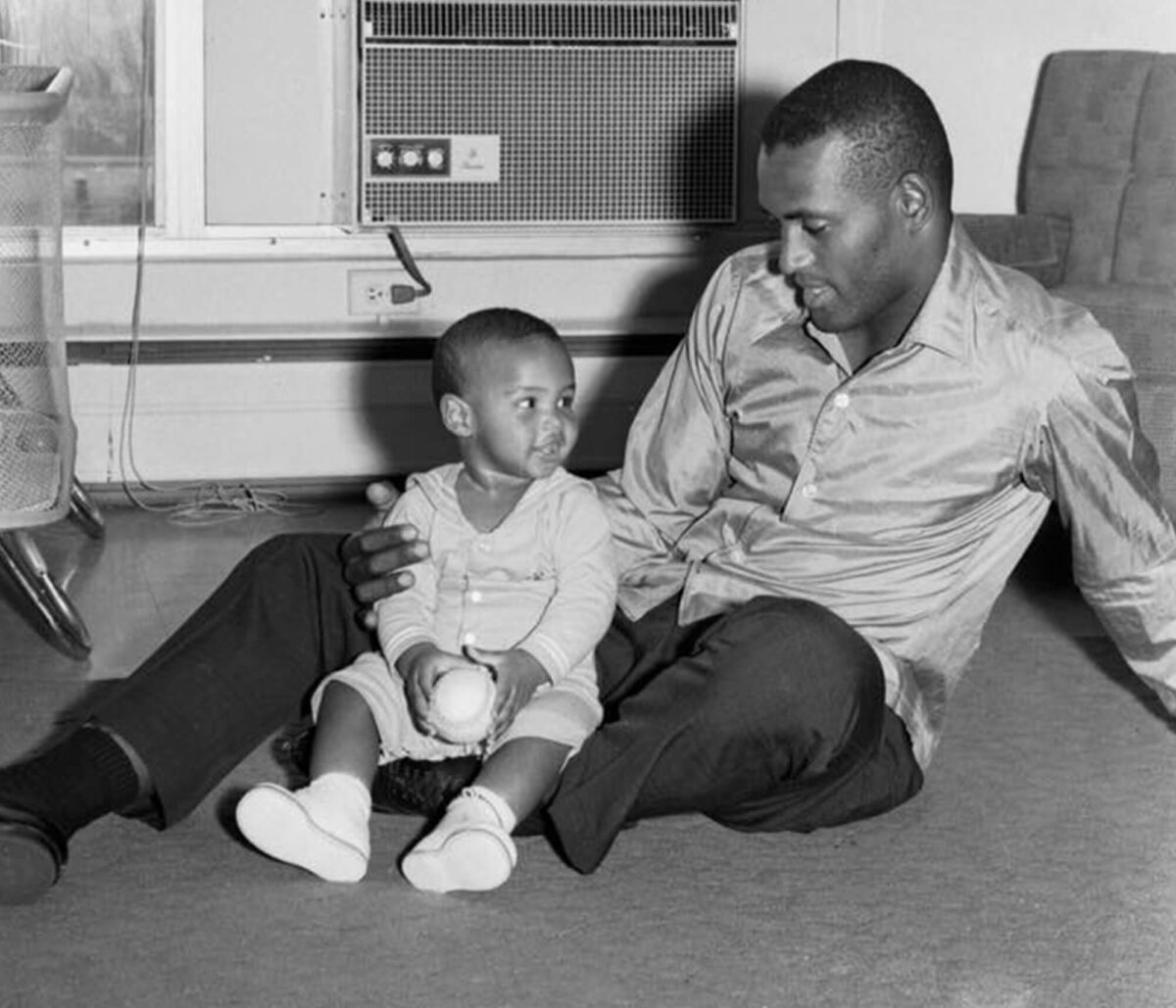

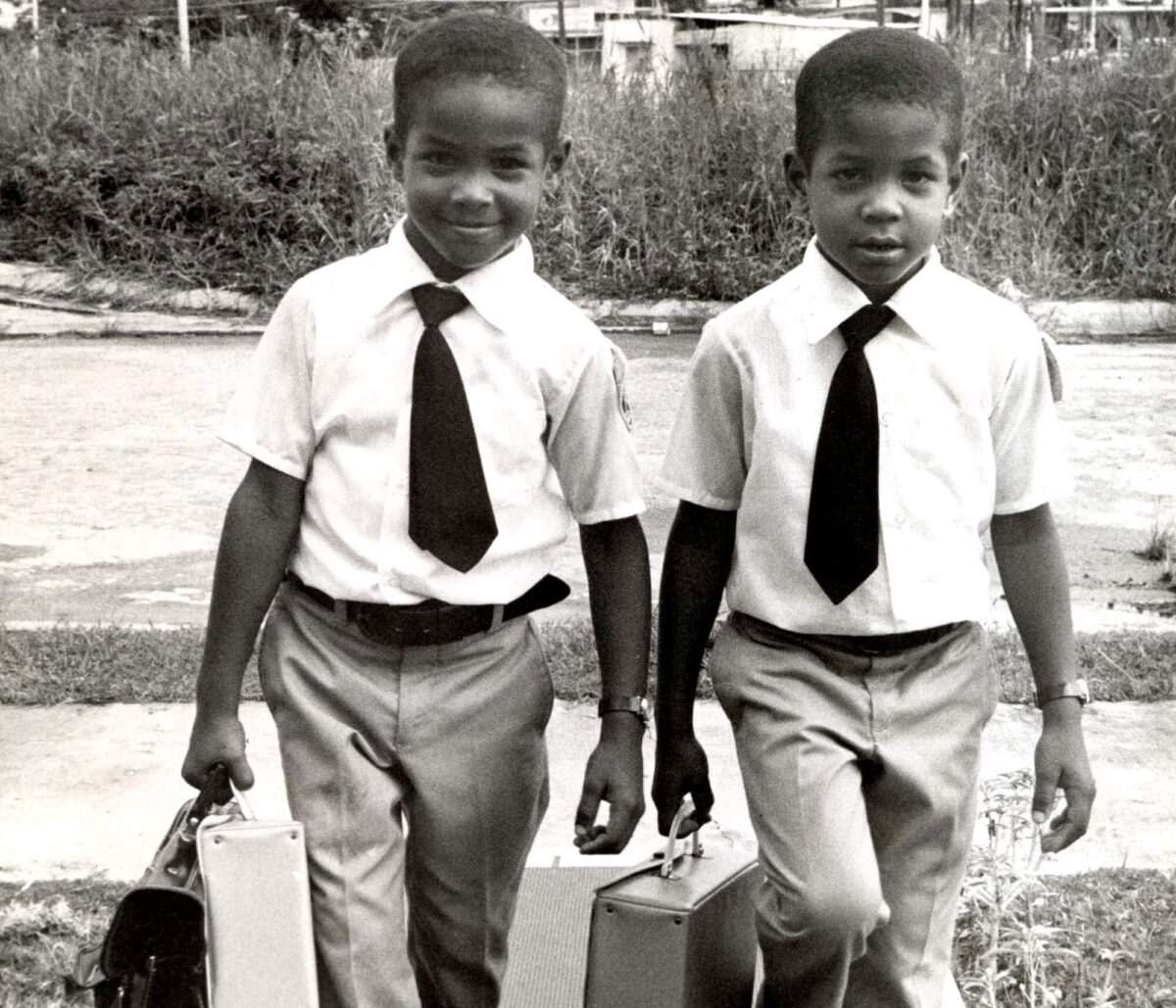

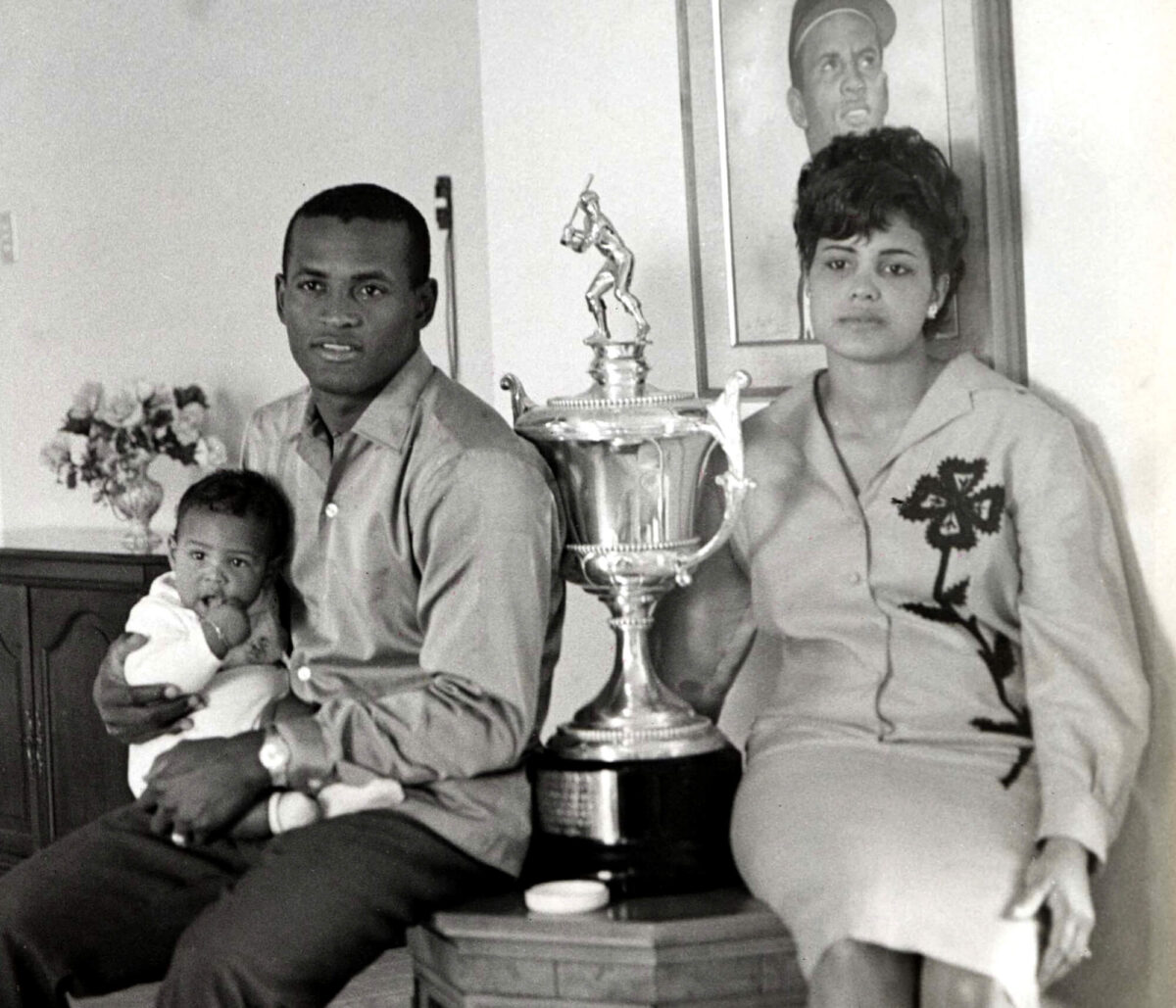

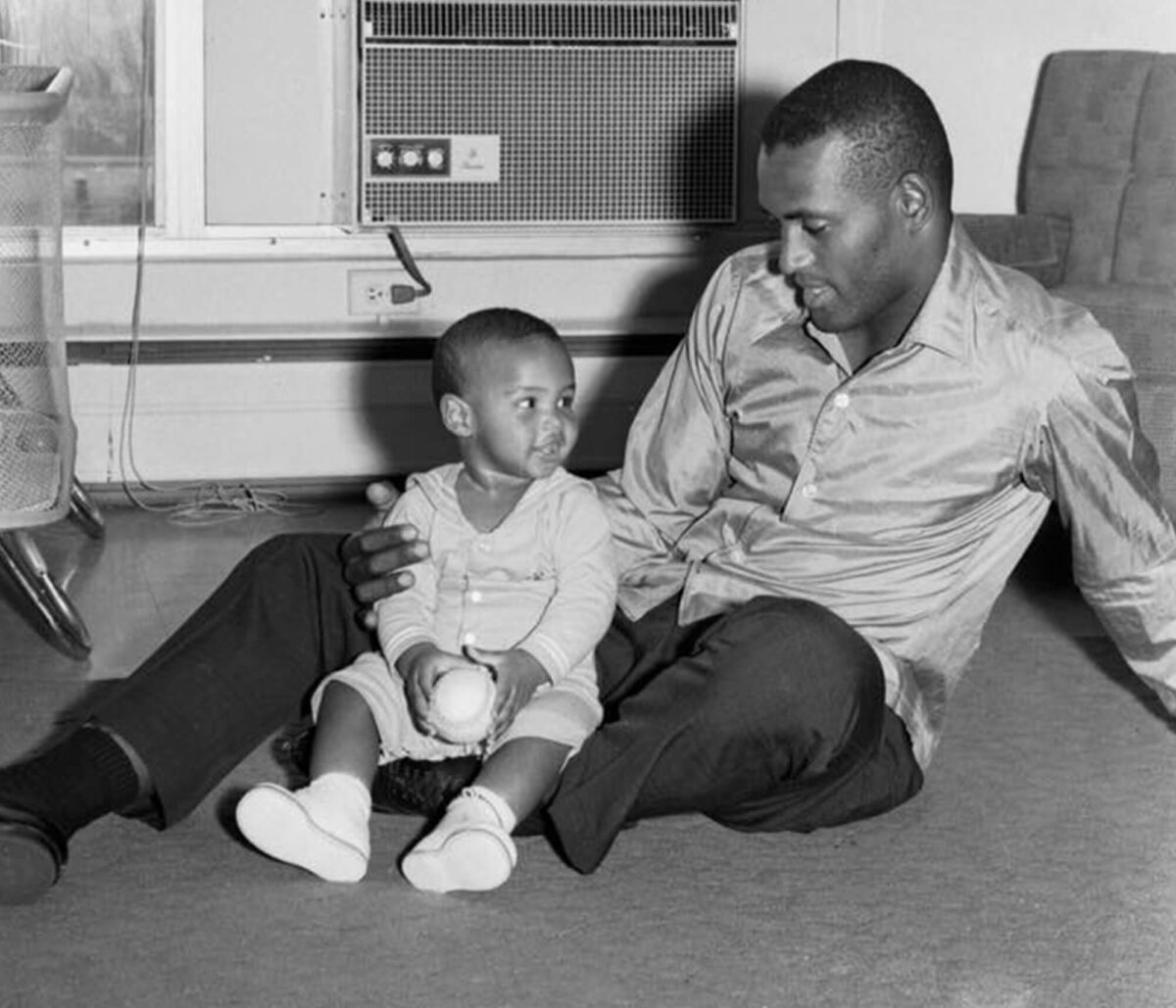

The wedding in November 1964 was a national event, with thousands lining the streets to see the procession. Roberto Jr. would come into their lives in 1965, followed by Luis in 1966 and Enrique in 1969.

By the end of his career, Roberto had joined the esteemed 3,000-hit club, won four batting titles, twelve Gold Gloves, two World Series, a National League MVP award, and achieved a .317 lifetime batting average. He struggled with sleep deprivation, and told his friend Luis Mayoral that “If I could sleep, I’d hit .400 every year.”

But for him it was never about the awards, or the stats, or the fame. It was always about service, making the world a better place. He was capable of bearing the huge weight of representing Puerto Rico and larger Latin America in the eyes of the white world, and he took that responsibility very seriously.

Managing the San Juan Senators, the team he had carried bags for all those years ago, was a highlight of his later life. His heart was always for his community, as he showed after the 1971 World Series when he addressed Luisa and Melchor in Spanish on TV:

“En el día más grande de mi vida, para los nenes la bendición mía, y que mis padres me den la bendición en Puerto Rico.” “On the greatest day of my life, to my children [I give] my blessing, and [I ask] that my parents in Puerto Rico give me their blessing.”

The 1972 holiday season was a dark one for Latin America. On December 23, a vicious earthquake struck at the heart of Nicaragua, just two weeks after Roberto and the Senators had been there for the Amateur World Series. The movement of the quake was horizontal, like something had woken up beneath the earth, and the cathedral clock in Managua jolted to a stop at 12:27 AM.

As the aftermath worsened, Roberto heard that shipments of supplies he’d sent to the country had disappeared in the chaos. He insisted on seeing the next shipment there himself to ensure that the Somoza regime distributed the aid appropriately.

The boys were sleeping at the Zabalas’ house. Robertito, 7 years old at the time, was always nervous when his father flew and often attempted to hide his plane tickets. As Abuela Zabala was tucking him in, he eerily told her that he thought the plane was going to crash. She told him everything would be fine, as any grandmother would.

Tragically and unforeseeably, she was wrong. On New Year’s Eve, December 31, 1972, the plane was overloaded and crashed into the ocean immediately after takeoff. It was one of the most surreal days in Puerto Rican history. Not only did Robertito have his premonition, but both Vera and Melchor had dark feelings that something was wrong, and those feelings were confirmed as the news spread through the island and the press.

In only two decades, from his first games at Sixto Escobar Stadium on the Isleta de San Juan to the horror off the coast of Piñones, Roberto built a legacy that has lasted to the present day. His body was never found, but his presence is powerfully felt on the island to this day. Schools, streets, parks, and other landmarks bear his name.

Here at the Roberto Clemente Foundation, we believe in Roberto’s power to affect powerful change today. He may not be with us, but we can carry on his legacy into the future.

As we celebrate Roberto’s life and extend his vision and mission into the future, it’s important not to lose sight of who made all this possible.

Vera and Roberto were married on November 14th, 1964. They were together for only 8 short years, immediately establishing themselves as one of the most striking and elegant power couples in popular culture.

Vera preferred the sidelines to the limelight, but her tasteful style and effortless poise made her an icon to those who paid attention. Today, she’s an unofficial elder stateswoman of Puerto Rico, and the guardian of Roberto’s legacy.

Vera also serves as the Goodwill Ambassador to Major League Baseball.

After the tragic loss of Roberto in a plane crash attempting to deliver aid to Nicaragua, it certainly would have been possible to move on, to stay in America and pursue a career, perhaps find love again and remarry.

But Vera didn’t choose that path.

Instead, she recognized the importance of Roberto’s vision and committed herself and her family to it.

It’s at least partially thanks to her that Roberto is remembered as much today for his humanitarian work as for his talent on the diamond.

It has been Vera’s guidance and tenacity that have guided us through these past 45 years.

She is the mastermind of the Ciudad Deportiva (Sports City) complex, presenting the Clemente Award each year, and illuminating the direction for Roberto Clemente Foundation.

It was Christmas Eve and evening was approaching, and Jean Fruth (photographer for the Baseball Hall of Fame) suggested that she leave soon so the family could go about their night.

But Vera insisted that she stay for dinner, saying “Now you have a family in Puerto Rico.” Jean also had the privilege of capturing the family’s annual observance at the crash site, and also got to participate in the family prayer.

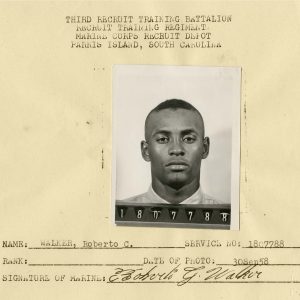

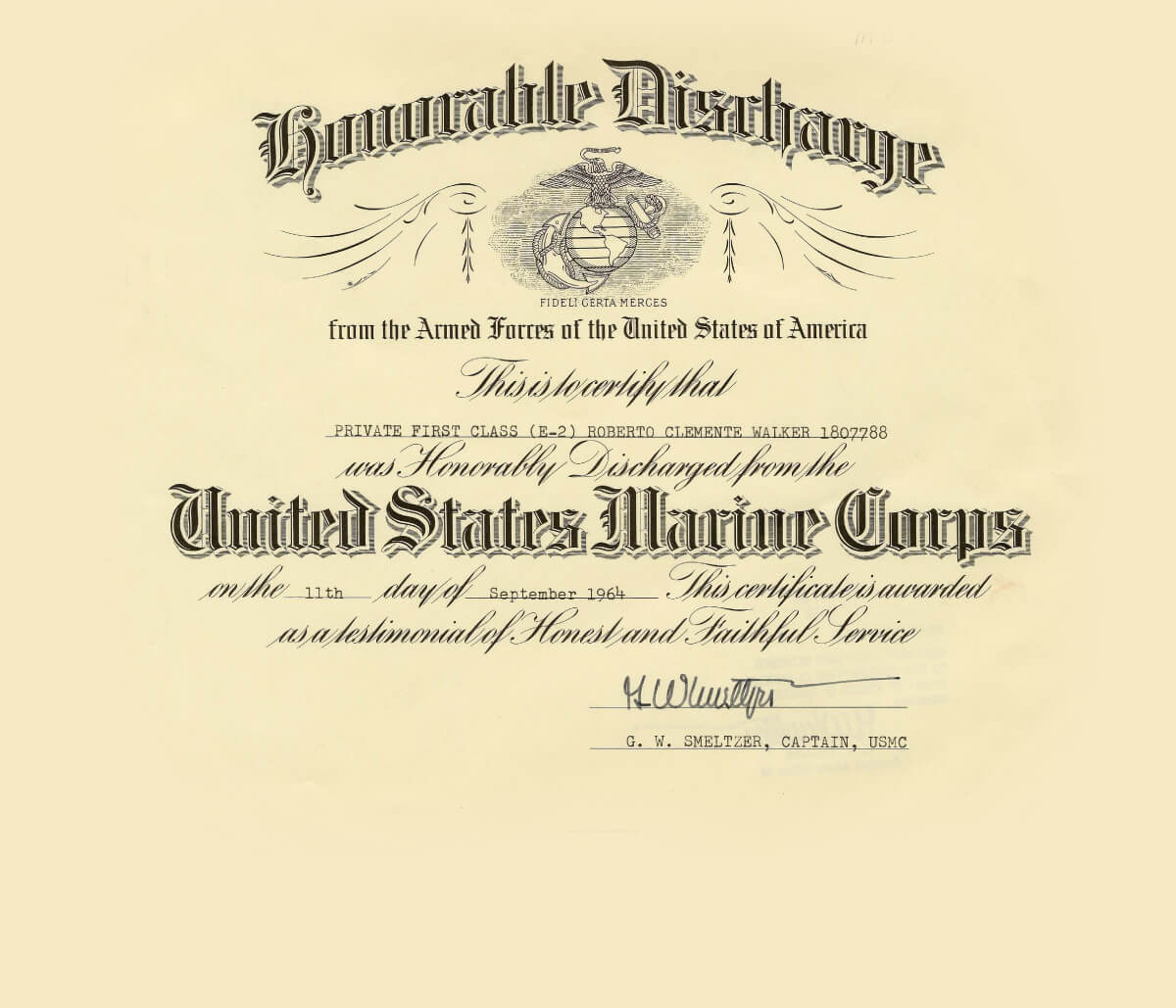

In the 1958-59 off season, while many major league players wintered in Puerto Rico and played ball, Clemente enlisted in the United States Marine Corps Reserve, spending the next six years in the military as an infantryman.

Roberto spent six months on active duty at Parris Island, South Carolina and Camp LeJeune, North Carolina. He ended up serving until 1964.

Today, Roberto’s military legacy is being recognized. He was inducted into the Marine Corps Sports Hall of Fame in 2003, and was inducted into the Puerto Rican Veterans Hall of Fame 15 years later.

In 2015, a bust of Roberto was unveiled at the Puerto Rican Veterans Memorial in Boston. The military was an important part of his life and his pride as a Puerto Rican and an American. Along with only 6 others out of the 130-member platoon, he was promoted to private first class.

The Clemente Foundation has a long history of working with various military branches in our relief and community outreach endeavors.

One key player on our team is Foundation Board Member Victor Rivera-Collazo, a retired Command Sergeant Major in the U.S. Army. He is one of our primary speakers and organizers of community outreach and baseball clinic programs.

We at the Roberto Clemente Foundation are committed to honoring and serving both active-duty and retired members of the armed forces.

The 3,000-hit club is one of the most exclusive honors in the sport. There’s no formalized award, just the objective facts of the public record. The most recent inductee was Albert Pujols in May 2018, the fourth player in history with 3,000 hits and 600 home runs, and only the second Dominican to make the club. Adrian Beltre was the first a year before, so it’s been a hugely exciting time for the Caribbean presence in baseball.

Pujols is one of our favorites here at RCF, and he makes no secret that his accomplishments over the past decade have been significantly motivated by the Clemente Award he received in ’08, which stands in a place of honor in his home. It’s amazing how much has happened these past 45 years.

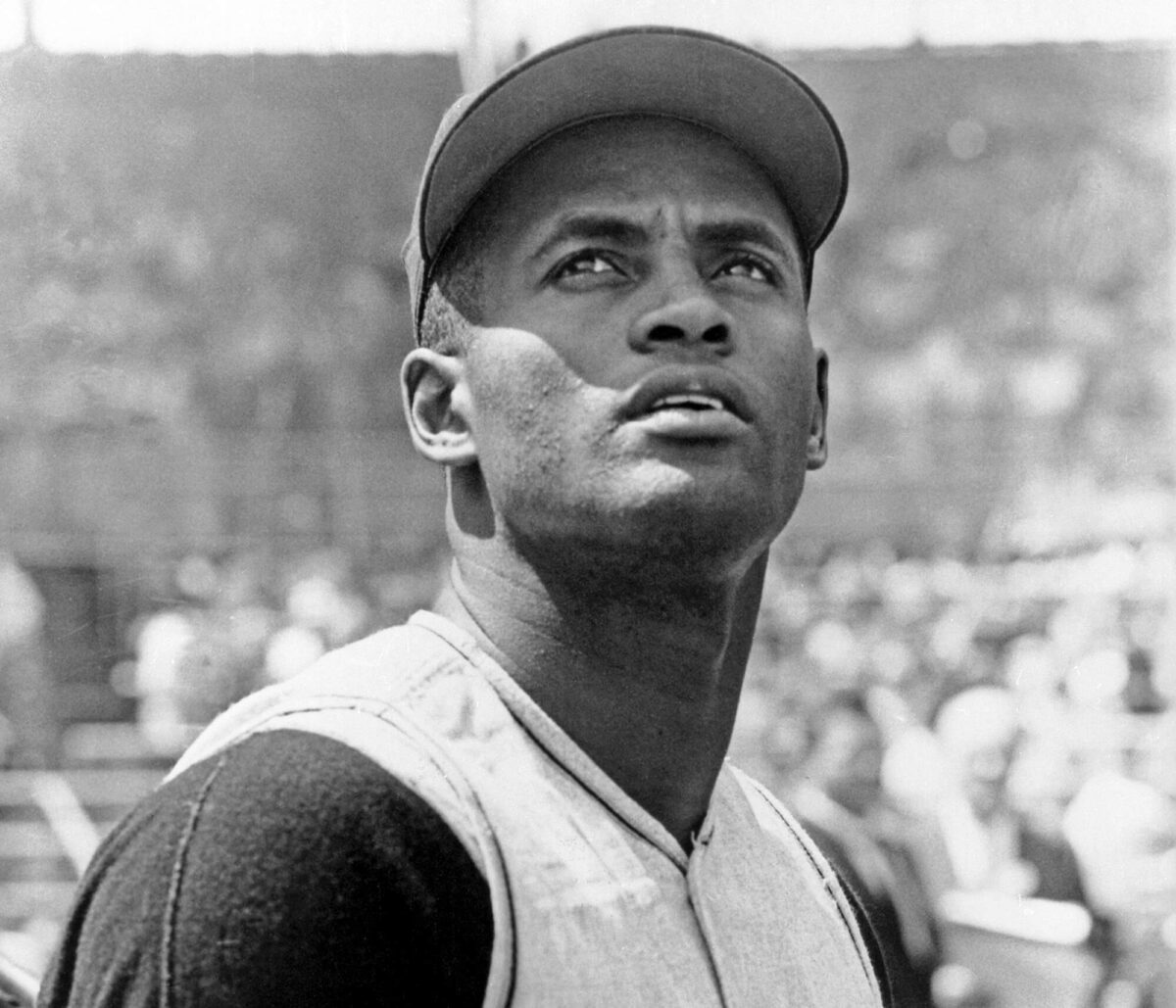

It was September 30, 1972. It felt like the dawn of a new age for Roberto, like his legend was just beginning to be written. There was no way to know that he would only be with us for three more months.

The Pirates were still glowing from their World Series win the previous year, with Roberto and Bill Mazeroski the only remaining players from their win in ’61. When Roberto’s 3,000th sailed over the heads of Yogi Berra’s Mets, it was a moment straight out of a classic movie.

When it comes to the 3,000-hit club, only the most hardcore fans and scholars could name the pitchers who were on the other side of those iconic moments. Not so with Roberto.

Jon Matlack is a crucial element of the Roberto legend, thanks to his presence on the mound that day. Matlack was a strong pitcher, and Roberto struck out badly in their initial encounter. He made sure not to let it happen again at the bottom of the fourth.

Attendance was slim that day, and the audience rooting for the Pirates were mostly die-hard Clemente fans, a few dozen of whom had flown up from Puerto Rico specifically for this occasion. Among them was a photographer from San Juan, Luis Ramos, who captured the whole day in a famous sequence of pictures.

Roberto, ever the showman, turned to the crowd and removed his helmet, thanking them for their support on his incredible journey. Matlack had no idea what was happening, until he looked at the scoreboard and saw the massive blinking number 3,000.

Matlack was a great technician with a keen eye for technique, and he observed that “…his hands never committed [until the last moment]. He would take a big stride, but his hands always stayed back, in a cocked position.” This unusual method combined with his impeccable timing made Roberto a force to be reckoned with, even up against some of the game’s strongest pitchers.

When he was given the ball to keep after the game, he wrote “off Matlack” on its surface in pen. The 3,000-hit club was a tiny group of 10 at the time, with only Hank Aaron, Willie Mays, and Stan Musial batting 3,000 since 1950.

Out of the entire pool of players in the club (32 as of this writing), Roberto is the only one to make 3,000 hits and no more. This eerie coincidence has been often commented upon.

The sheer statistical unlikelihood, of hitting that milestone and dying so soon after, is enough to give pause to the strongest spiritual skeptic.

Three years later, Vera Clemente told the New York Times, “[In 1972] he said, ‘If I don’t hit it now, I don’t hit it ever.’ I don’t know if he knew or what.” Unfortunately, nobody knows why things played out the way they did on New Year’s Eve.

What we do know is that Roberto would have wanted us to carry on his real mission: to build nations of good in a world that is crying out for meaning and truth.

Roberto had a close circle of friends, and perhaps the single closest in America was Phil Dorsey, a black man from Pittsburgh who played a number of vital roles for Roberto, from valet to babysitter. They met early in his days as a Pirate, and he set Roberto up with a place to stay with Stanley and Mamie Garland, who he would come to love dearly as his stateside “parents.”

A few days after the crash of Roberto’s plane, Phil was sitting outside the house with Luis Mayoral, another close friend of Roberto’s. They were in Luis’s car, watching folks coming and going to pay their respects and offer condolence to Vera. It was deep into the night, and Phil told a story about the number 21.

“I will never forget that before the 1955 season opened in Pittsburgh, Roberto and I went to the movies. While waiting for the movie to start, Roberto took a piece of paper and wrote down his full name: ‘Roberto Clemente Walker.’ And he told me that his name was made up of 21 letters and that he would ask the Pirates to give him that number.”

The details vary slightly depending on the source, but it’s a compelling scene and as good a reason as any for why Roberto jumped at the opportunity to change his number. On the official side, the 21 legend begins with an obscure center fielder named Earl Smith.

When Clemente was a rookie, his jersey was emblazoned with #13. If there could be an opposite number to 21, it may well be 13. Where 21 is elegant and subtle in its associations, 13 is crude and ugly, associated with a silly complex of superstitions and “bad luck.”

Earl Smith holds a place in baseball history as the player who wore 21 before Clemente, and he certainly didn’t have much luck in his brief time as a Pirate. Over the course of five games and exactly 21 plate appearances, Earl only hit the ball once, so he was sent back to the Minor Leagues. The number was given to Roberto, and an icon was born.

Today, 21 is probably the single most famous number in Latin America. No other number is so automatically and permanently connected with a particular person and the values he lived out. Stateside, it’s one of the most important numbers in baseball culture, with many players at every level wearing it pride, and a long-running debate over whether it should be retired in the majors.

It has lent itself as a title for a comic book by Wilfred Santiago and a stage play by Luis Caballero. Public artwork featuring Roberto can be found dotted throughout the world. Children research him for school projects and declare him their hero. We couldn’t be prouder of that legacy.

It would be easy to simply capitalize off of Roberto’s legacy, but we are called to a higher goal.

Roberto’s example demands a response from us, and we are realizing his dream by doing what he did: reaching out to help the poor and the needy, and spreading his story and his passion for baseball far and wide.

With your help we can continue Roberto’s work into the future, impacting future generations with love and support.

In 1971, Willie Mays received the award as well as Brooks Robinson in 1972, which was then called the Commissioner’s Award. In 1973, the award was given to Al Kaline as the Roberto Clemente Award for its humanitarian qualities.

Thankfully, over 40 of the Clemente award winners are still with us today. Most have retired, but are still active and doing good work for their communities. We hope to have as many of them present as possible for the Clemente Hall of Fame dedication ceremony in November 2018. Our Hall of Fame is a celebration of these humanitarian efforts. Our hope is that we can help cultivate the next generation of world-changers.

The Roberto Clemente Award stands out among the other MLB awards. Award winners embody Roberto’s values on the diamond and in the community. The Roberto Clemente Award has established itself as one of baseball’s most prestigious humanitarian awards.

Award winner Albert Pujols’s Roberto Clemente Award occupies a place of honor in his home away from his many other awards.

“It’s the greatest award you can win… This will go front and center in front of anything I’ve ever done on the baseball field.”

– Anthony Rizzo, 2017 Winner

When he was asked what question he would ask Roberto if he had the chance, Albert Pujols said: “Why did you get on that plane to serve those people in Nicaragua who you did not know and had never met?”

Pujols then gave a suggestion for Roberto’s hypothetical response: “‘Because it was my responsibility.’ I feel the same way. It is my responsibility.”

Roberto recognized very specific wrongs in the world, and was compelled by a higher power to do what he could to make it right. It was his responsibility, and we are all called to use our talents to answer that same call.